Around the world with a young Swiss explorer in 1900

Long before he became president of the ICRC, Zurich-born Max Huber travelled the world for two years. The young lawyer documented every step of his adventure. Now, over a century later, his grandson has brought the records and photographs to light.

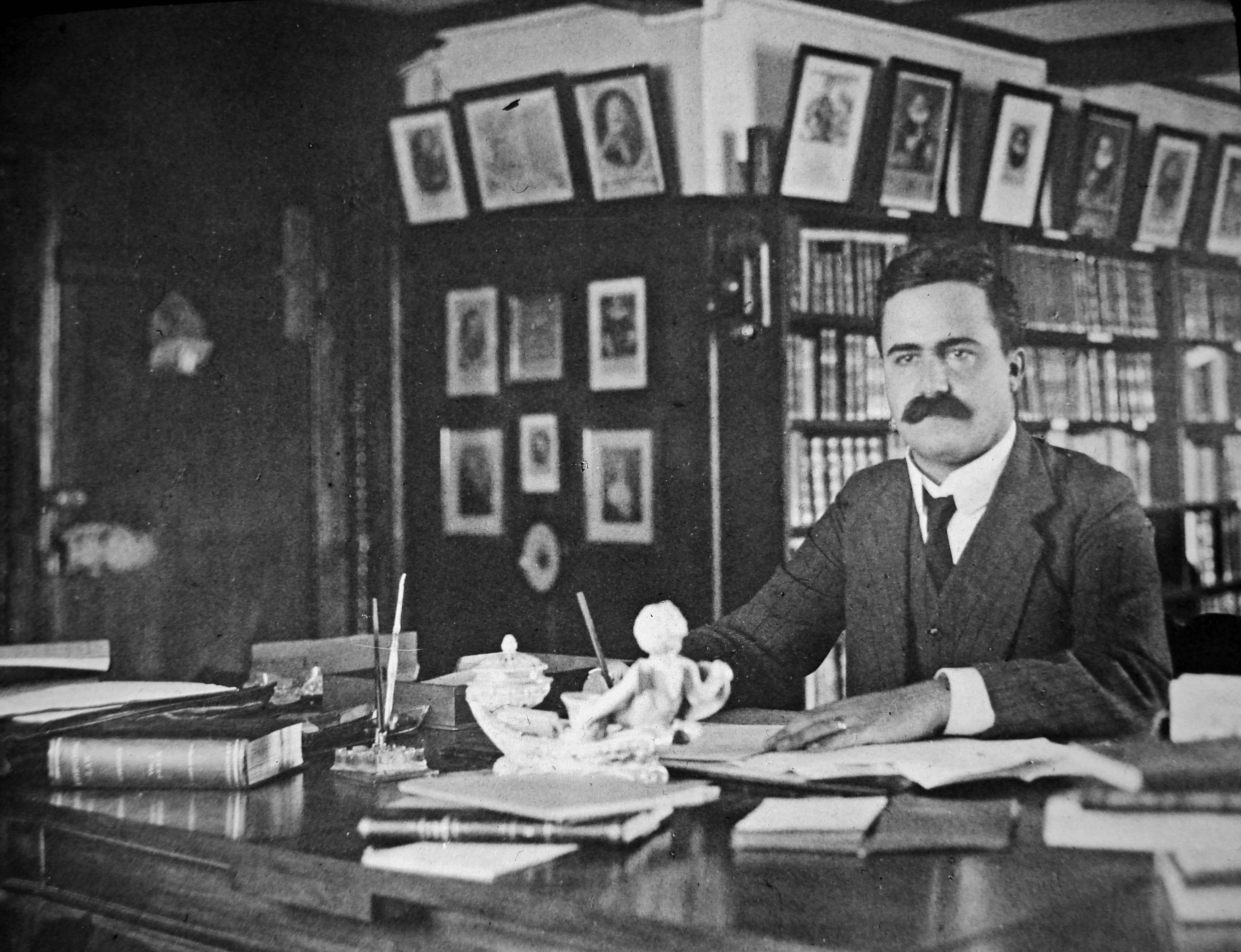

Today, only a few Swiss will recognise the name Max Huber. But in Ossingen, a small village of 1,700 people in canton Zurich, he is a local legend. The striking 13th century Wyden castle used to be his home, and since his death on January 1, 1960, it has remained almost untouched. His grandson Ulrich Huber, born in 1939, recently showed me around the castle which has now become a small family museum.

Max Huber was born in 1874. He quickly climbed up the career ladder as a lawyer and diplomat. From 1902, he worked as a professor of law and served as an adviser on foreign policy for the Swiss government which required him to represent Switzerland at various international conferences. From 1920 to 1932, he was a member of the International Court of Justice in The Hague, and from 1928 to 1944 he served as the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). After his term, on December 10, 1945, he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the ICRC as honorary president.

The catalyst to his amazing career was Huber’s trip around the world from May 1900 to December 1901.

“I think my grandfather got key inspirations for his work as a diplomat during that trip,” says grandson Ulrich Huber.

Max Huber’s journey took him through Russia, Japan, Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Australia and China before he finally ended up in the United States. He had hoped to embark on this journey as an official envoy of the Federal Political Department. The Swiss government did not grant him that mandate but gave him letters of recommendation that opened several doors for him.

Ulrich Huber takes me up to the very top of the castle’s tower where his grandfather’s library is located. One floor down, he surprises me by rolling a carpet aside. Through a trapdoor we descend into a dark room where part of the family archive is stored. Throughout his journey, Max Huber regularly wrote to his family. He sent his diary home in instalments (or portions) and later published an abridged version as a book in 1906.

The book includes three analytical chapters which talk about Siberia’s commercial landscape, the prospects for Swiss exports to China, Japan’s transition to a constitutional monarchy and democracy in Britain’s colonies in Australia. These chapters reveal that Huber processed many of his impressions only after his trip and turned them into carefully crafted prose.

Max Huber sent home more than just words. He kept a precise log of every single document and item he sent home, while back in Ossingen, his relatives meticulously recorded everything that arrived.

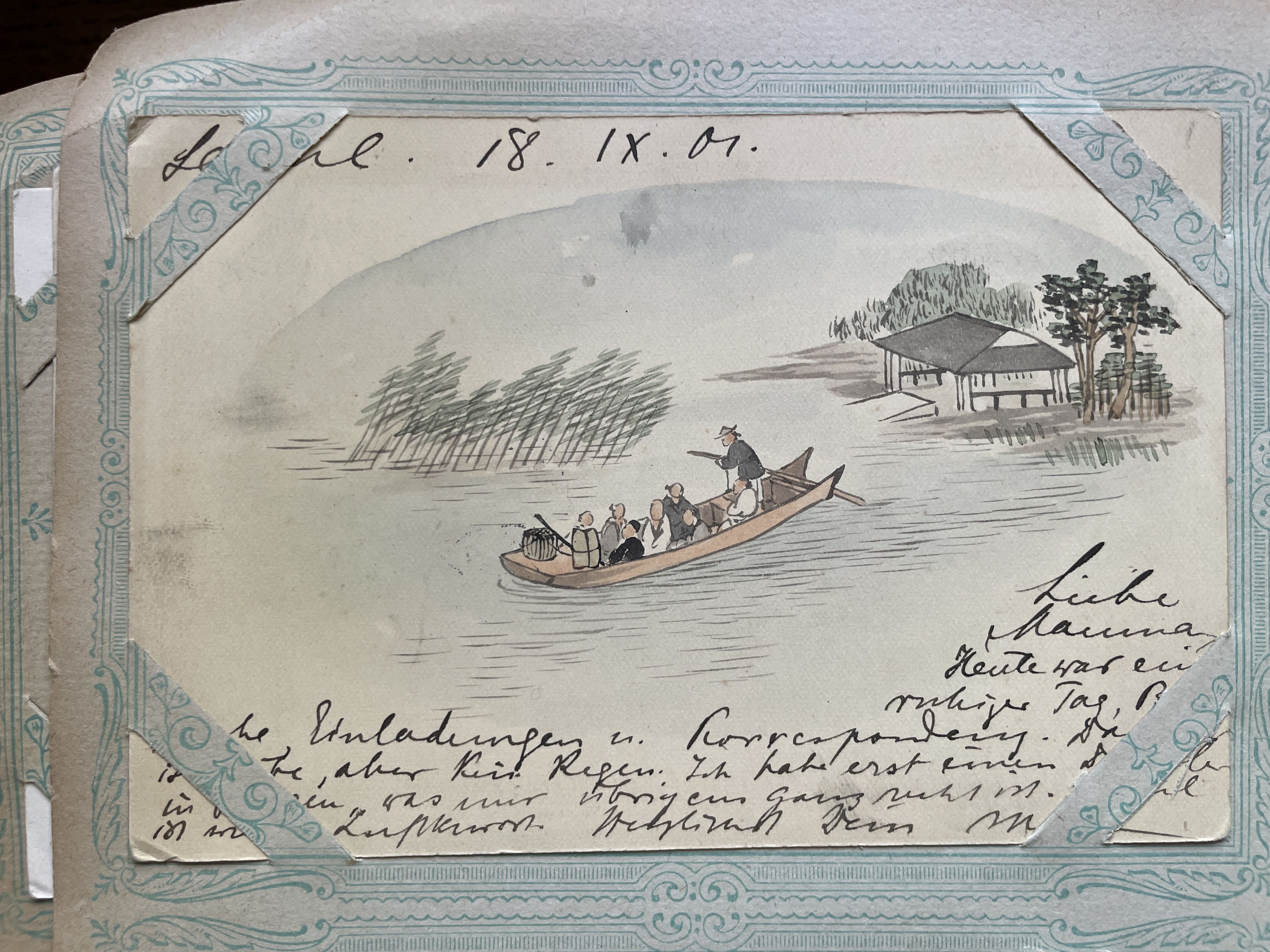

In November 1900 alone, he sent six packages with photographs from Yokohama: a delicate letter written on Japanese wooden paper, four illustrated postcards, several pages from his diary and 12 postcards of temples, teahouses and parks. But that was just the beginning. In Japan, which the young globetrotter was particularly enamoured with, he bought sculptures and cast-iron temple lanterns nearly two metres tall.

Most impressive are the postcards to his mother. “Today I arrived in Saigon. The vegetation is tropical, and the botanical garden is amazing. A truly grand promenade. However, the hotel is rather modest. I received a very warm welcome from the Eberhard family as well as from many other Swiss here. The heat is horrendous and feels like being in an oven,” reads one postcard dated January 4, 1901. Huber often spread his messages across several postcards which he occasionally embellished with his own illustrations.

Max Huber travelled with a Kodak camera using glass plates as a medium. Lighter roll-film cameras were already available at the time, but their image quality left much to be desired. He also purchased photographs along the way and regularly sent them home.

Thanks to the wealth of material, it is possible today to retrace Huber’s steps in remarkable detail. His grandson has sifted through more than 3,000 photographs and thousands of postcards to compile a comprehensive documentary.

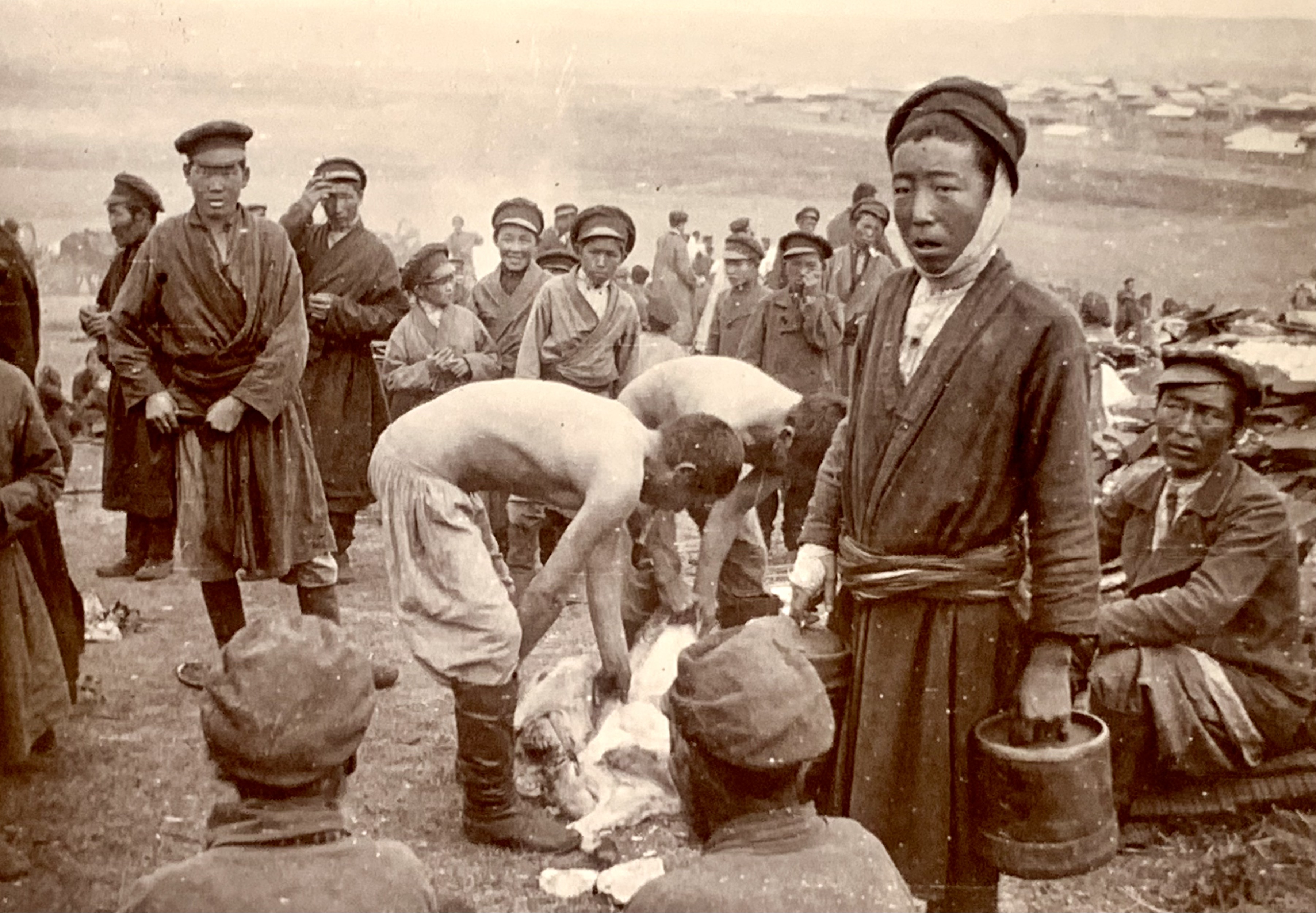

He mainly travelled by ship or train and sometimes by horse-drawn carriages. Thanks to his connections he often found himself in interesting situations. In Russian Irkutsk the director of the ethnographic museum took him to a traditional offering of the Buryats, the biggest ethnic minority in Siberia. Huber even managed to capture key moments of the ceremony with his camera. How he personally experienced this ritual is not known.

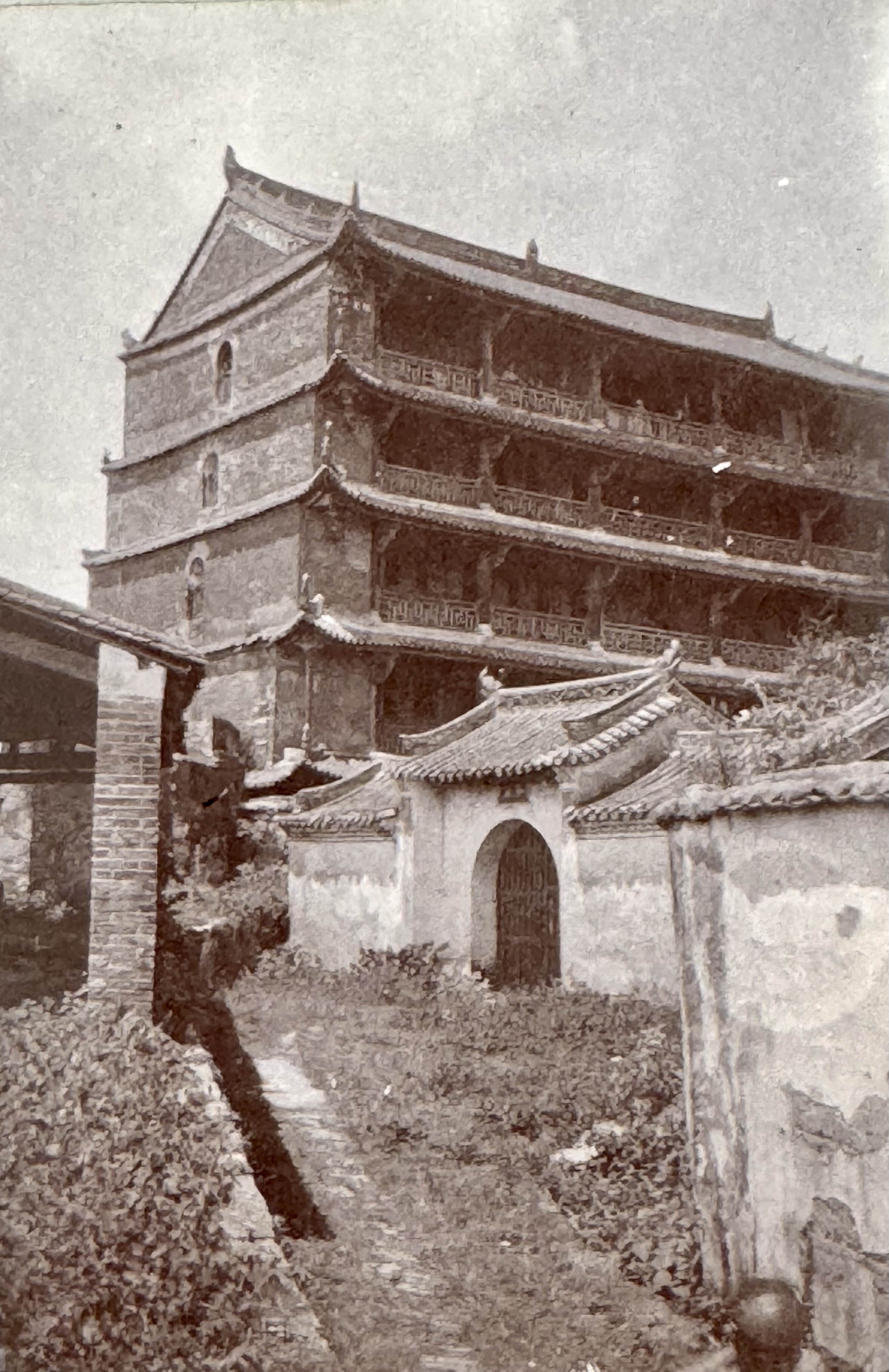

Huber often struggled with local traditions as reflected in his impressions of Canton (today’s Guangzhou).

“The houses were clean, but the canals, which were crossed by steep bridges, were little more than open sewers. On top of that there were countless open kitchens where chickens, suckling pigs, meatballs and fish were fried in disgustingly smelling grease. In rather uninviting taverns, oddly coloured drinks were served.”

In China, Huber experienced a tricky situation. Just before his arrival, the so-called Boxer Rebellion – a violent conflict involving Western superpowers – had come to an end. Reporting from northern China in September 1901, he wrote critically: “Some of the European and US troops lived like vandals.”

Although Max Huber could enjoy all comforts money could buy at the time, travelling was cumbersome. He struggled with the heat which led him to skip India and limit his stay to a visit of a tea plantation in the highlands of what was then Ceylon.

His father had urged him to visit Ceylon, apparently because he owned shares from a deceased friend there. The rewards for his efforts were the breathtaking train ride to the highlands and the pleasant climate.

Max Huber was part of a growing trend that had spread across Switzerland since 1860. Travelling the world had become an educational and leisure pursuit for the rich. Huber joined the ranks of fellow adventures like chocolate magnate Suchard, who set off in 1973, naturalist Johann Rudolf Geigy in 1886 and Burgdorf photographer Heinrich Schiffmann in 1897.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.