Stanislaus von Moos: Switzerland is an architectural ‘Disneyland’

Art historian Stanislaus von Moos, winner of the 2023 Swiss Grand Award for Art, sees Switzerland as an architectural laboratory of sorts – one that has produced its fair share of flops.

Stanislaus von Moos wrote his first book aged 28 while he was teaching at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Entitled Le Corbusier: Elements of a Synthesis and published in 1968, it was the first comprehensive critical survey of the Swiss-French architect’s life and work. The book went on to become the standard text on Le Corbusier.

During study trips with his students, von Moos discovered the garish mishmash of North American suburban architecture.

“The book Learning from Las Vegas, by the architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, was an eye-opener for me,” he says. “It provided a vocabulary that made everyday American life comprehensible.”

Over the years, von Moos has come to appreciate the logic behind strange places and their ugly beauty. Now a renowned professor, the art historian and architecture theorist describes Switzerland as an architectural “Disneyland”, on the grounds that Swiss building culture is increasingly focused on show and spectacle.

In the video below, Stanislaus von Moos takes us on a tour of his Doldertal apartment in Zurich, built in 1935.

Swiss experimentation in architecture

Von Moos taught modern and contemporary art at the University of Zurich from 1983 to 2005. He’s helped to shape generations of students. Many are now leading figures in the art world, including Martino Stierli, chief curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Initially von Moos’s ambition was to become an architect. After finishing high school, he studied architecture for two semesters at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. He soon doubted, however, whether he had the necessary talent, and enrolled instead in art history at the University of Zurich, with a special focus on the history of architecture. “I am quite comfortable today with having left hardly any material traces,” he says of his career.

Architectural self-realisation is anathema to him. “The production of ever more original buildings has become a problem,” he says. Thanks to the hype around Swiss architecture that he helped to trigger as editor of the magazine Archithese in the 1970s and 1980s, architects were propelled to regional and cantonal prominence. Sometimes they created immense structures that, in his view, would have been better left unbuilt.

As von Moos sees it, Switzerland’s wealth makes many things possible. “Switzerland is a kind of showcase for different building types in Europe,” he says. “In fact, there is an incredible amount of experimentation going on here. And the proportion of elaborately and expensively made trivialities is correspondingly large. This can be seen in the huge variety of designs of single-family homes and apartment blocks. And the further you move away from the centre, the greater the architectural confusion.”

Von Moos refrains from giving more specific examples but does mention the LAC Arts and Cultural Centre in the southern city of Lugano. In 2001, some 130 firms entered a competition to design the building, which was ultimately won by the Ticino architect Ivano Gianola. Von Moos describes the building as having a “dazzling basic concept” that was never fully thought through architecturally and that was executed at the sketch stage because the money was obviously available.

It is also striking, he finds, how discreet Swiss banks are when it comes to architecture, despite their riches.

“Banks are not interesting clients for architects in this country,” he says. “They have left hardly any significant marks on the nation’s cultural heritage in the last 70 years.”

Carefully executed buildings

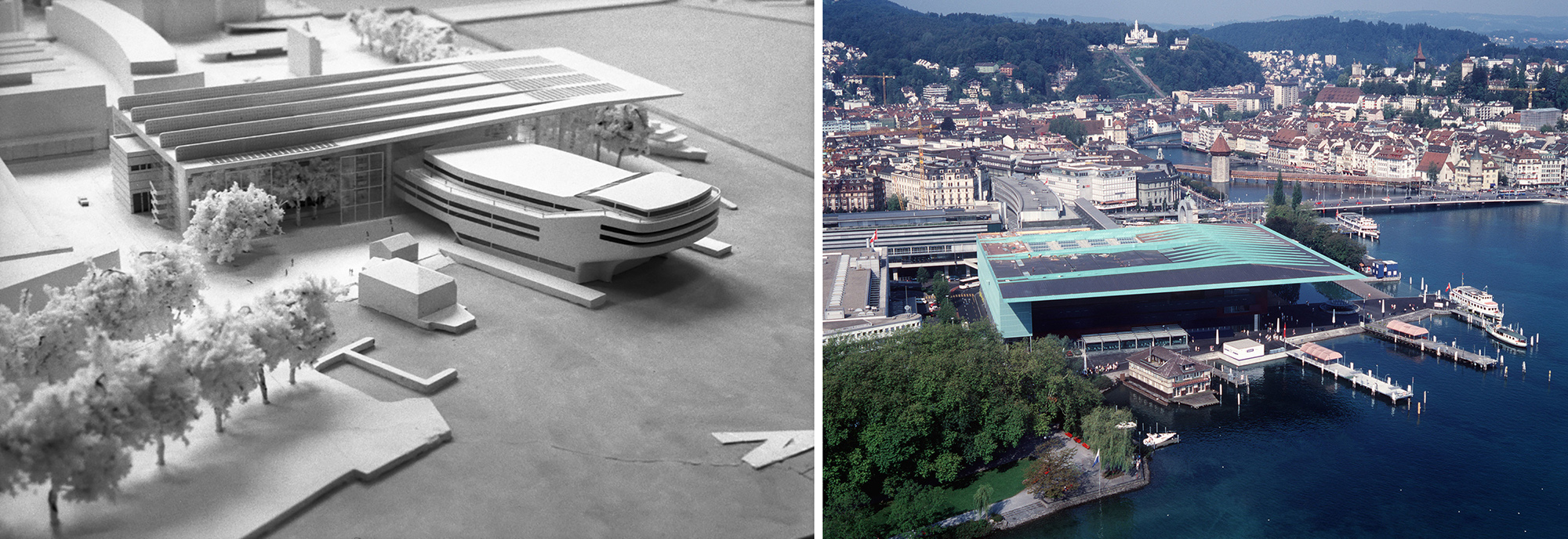

Von Moos is convinced that good architecture is only possible with good building developers. A prime example of this is the Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre (KKL Luzern), which sits right by the lake in the heart of the city. Business consultant Thomas Held accompanied and supervised the entire process with military precision. A quarter of a century later, Jean Nouvel’s imposing structure remains impressive – even up close.

Von Moos is full of praise for the precision and care with which the building was erected, and for the craftmanship and boldness of the design. This is precisely what is often lacking in modern architecture: careful execution. It’s true, he finds, of the creations of Ticino architect Mario Botta, whom he otherwise holds in high esteem. But von Moos finds Botta focuses on size and shape while paying less attention to detail.

Star architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Basel, meanwhile, come off better in this respect. Like Botta, they have built all over the world, from Paris to Beijing. “I don’t love everything they do,” says von Moos. “But I have never seen a building [of theirs] that was not carefully thought out and executed.”

Together with the architect Arthur Rüegg, von Moos dared to select 25 buildings from around a total of 570 Herzog and de Meuron creations for an upcoming book, Twentyfive x Herzog & de Meuron. In it, Rüegg and von Moos explore the architects’ working methods and their ambivalent view of the built world.

A soft spot for Le Corbusier

Von Moos developed an early interest in architecture, and notably in Le Corbusier. His own father authored the first article on Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut, a chapel in Ronchamp, France. Then, when he was just 17, von Moos came across a copy of Sigfried Giedion’s short book, Architecture, You, and Me: The Diary of a Development. It became like a Bible to him. Here was someone who was writing about people who wanted to change the world through architecture, and good architecture at that. First among them was the great Le Corbusier.

Together with a friend, von Moos jumped on a Vespa and set off to see Le Corbusier’s La Tourette monastery near Lyon and the Unité d’Habitation, a 12-storey monolith of 337 apartments in Marseille. He describes the Unité as a “place of pilgrimage” that he visits every five years. Later, as a student, he would work as an assistant for Giedion and get to know the Doldertal Houses, a group of modern apartment buildings in a suburb of Zurich. They were designed by architects Alfred and Emil Roth, in cooperation with Marcel Breuer, in 1935.

The Doldertal Houses were a manifesto of the new architectural movement in Switzerland. They celebrate a light-flooded homeliness and offer a view of the canopy of trees in the Wolfbach ravine, and yet have nothing to do with the surrounding built environment. Von Moos himself has been living in one of the Doldertal Houses since 1986.

Edited by David Eugster. Translated from German by Julia Bassam/gw.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.