Swiss authors offer critical take on humanitarian aid

The daughter of a former civil servant with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Neuchâtel writer Fanny Wobmann takes a critical look at humanitarian aid sent to Africa. Her approach reflects a broader trend among Swiss authors.

One winter day Fanny Wobmann inherits a stretch of forest. The six hectares which she shares with her two sisters are situated on the slopes below La Chaux-de-Fonds, the town where she was born 40 years ago.

“Suddenly I was the co-owner of a piece of nature. This was awe-inspiring, beautiful and unsettling,” she writes on the first page of her book Les arbres quand ils tombent (As the trees fall). Her father, a lumberjack, had bought this green terrain, then bequeathed it to his daughters. It was a precious gift for Wobmann who is very fond of nature.

While roaming in this inherited forest, Wobmann is suddenly confronted with the notion of “borders” – those of a territory that now belongs to her. From there, her story forks and leaves La Chaux-de-Fonds. The reader is transported to Africa: Senegal, Rwanda and Madagascar, moving back and forth between these countries and Switzerland.

Europe at the time had its colonies in Africa. Switzerland had its humanitarian aid, generous, sometimes self-serving, sometimes misdirected. These contradictions have been highlighted by Swiss authors Lukas Bärfuss, Anne-Sophie Subilia and now Wobmann.

Caring about others

Wobmann is a comedian and a playwright too. One of her previous novels, Nues dans un verre d’eau (Naked in a glass of water), published by Flammarion in 2017, has been translated into German and Russian. She has received several grants and has been in residence at the Michalski Foundation in Canton Vaud this June, to work on her new book on mother figures.

“I’ve just been announced as the winner of the 2024 Swiss Payot bookstores’ prize for As the trees fall,” Wobmann says proudly. With a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Neuchâtel, she is interested in feminism, equal opportunities, integration and, above all, race. Not without reason. Living in Africa for four years opened her eyes to the harm “white domination” can cause.

More

Newsletters

Her parents not only bequeathed her part of a forest, but also a strong altruistic urge. As she explains, this has led her “to respect other people and to be humble, learning not to be pushy”. One day, her father, who had studied at the intercantonal Forestry Training Center in Lyss (Canton Bern), came across an advertisement for a job in Senegal. It had been put out by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) which is part of the foreign ministry. He applied and got the job.

Strict racial hierarchy

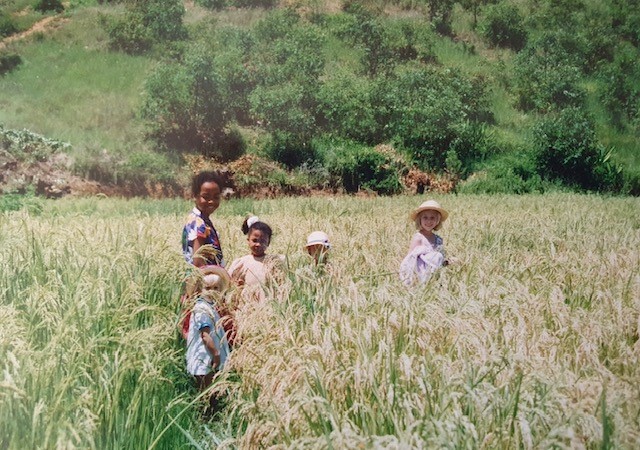

So, there he was in Senegal accompanied by his wife, teaching forestry. Very soon he was faced with the problems arising from the strongly hierarchical relationship between Whites and Blacks. He also had to deal with the stereotypes around humanitarian programmes, which put Switzerland at the peak of perfection, despite its flaws. Later, he continued working for the SDC in Rwanda and Madagascar, where Wobmann spent part of her childhood and adolescence.

Wobmann had not been born yet when her parents moved to Senegal. So it is their stories they told that she recounts in her book, which is a blend of diary and investigation. She recounts the meeting her parents had, shortly after their arrival, with a Swiss development worker tasked with welcoming them. What he said was shocking. The man explained “with self-assurance and a knowing little smile, how difficult – but also how very useful – SDC’s work is, considering the incompetence and stupidity of the Senegalese political system”.

Humanitarian aid with badly chosen aims

Years later, in order to find out more about the SDC missions, Wobmann went to see a Swiss friend of her parents who knows Africa well. “Like us, she had lived in Madagascar, but she had a more politicised point of view on the country’s situation,” the author explains. “She told me very clearly that the local people didn’t want that humanitarian assistance, because it didn’t meet their needs. The aid was essentially for the benefit of the Malagasy state, absolving it of any responsibility for its citizens.”

Subilia, another Swiss author writing in French, reaches a similar conclusion. In her novel The Wife, which came out in 2022,she describes the daily life of a representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and his wife in Gaza City under Israeli supervision. The story is set in 1974. A question arises, still very relevant today: what is the point of distributing humanitarian aid to populations threatened by war and famine?

Th author puts the somewhat disheartening answer in a Palestinian woman’s mouth. Referring to her incarcerated fellow-countrymen in Israeli jails, she tells the ICRC representative: “You are useful to the Israelis, because all you do for their prisoners is the very least they have to do”.

Bärfuss, a writer from German-speaking Switzerland, tackles the aberrations in the humanitarian system in A Hundred Days, A Hundred Nights. This book came out 15 years ago and is set in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide. The humanitarian aid provided by the SDC at the time is also called into question.

Safety net

“I wonder how a democratic country like ours could agree to open an office for cooperation at the centre of a dictatorship,” Bärfuss told SWI swissinfo.ch back in 2009. “Believing that one can remain apolitical in these conditions is foolish. Our aid went to a minority, to the people in power (obviously!), the same people who later committed the genocide. The poorest, those who really needed us, didn’t gain anything.”

Like Subilia and Bärfuss, Wobmann knows that humanitarian action suffers from a number of shortcomings. Nevertheless, she defends its merits. “Humanitarian assistance remains a safety-net, it prevents the most disadvantaged from giving up all hope,” stresses Wobmann.

Text edited by Samuel Jaberg/op

Adapted from French by Johannes Waardenburg/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.