‘Without the heroin programme I’d probably be dead’

Switzerland has distributed heroin to addicts legally for the past 20 years. Around 1,500 people receive the drug under supervision. One of them is Evelyn G., an addict for almost 30 years, who says the rationed drug helps her keep her life together.

“I am and always was a ‘sensitive’ type: it’s horrible, when all your feelings hit you unfiltered and you can’t protect yourself. Even as a child I was thin-skinned”, says Evelyn.

Already as a teenager, the 55-year-old began drinking. “I didn’t really like the taste, but I did like the effect.” Then she tried amphetamines, cocaine and finally heroin. “I felt sick, but heroin gave me a feeling of protection and warmth, and I was able to cope better with people.”

Evelyn has been in the heroin programme for nearly 20 years. She gets the drug she has been consuming for half her life at a controlled distribution centre in Bern. Around 1,500 patients across the country are receiving the same heroin-assisted treatment, which is intended for heavily addicted, long-term drug users.

Every day, Evelyn gets slightly less than half a gramme of essentially pure heroin, which she injects under the supervision of the care team, once in the morning and again in the evening. Her body craves the substance. Each time she looks forward to it. She is “100% convinced” that without the programme she would have been dead long ago.

More

Where Evelyn gets her daily fixes

Evelyn grew up with two younger siblings in canton Bern and Aargau. Her father was a doctor, while her mother taught gymnastics and music. After leaving school at 19 she went to work as an au-pair in London, where she tried out cocaine and “speed” and also had her first encounter with heroin.

“I was curious and did not see it as an escape [from reality], but was fascinated by it because I felt different,” she claims.

When she came back to Switzerland she went into nursing, got her school leaving certificate as a mature student, and finally started studying German literature at the University of Bern. During that period, she stuck mostly with cocaine. “I said no to heroin, because I knew how dangerous it was.”

When she was 27, her mother became ill and died in the space of five months. It was a huge shock and a turning point in her life. “Without heroin I would not have got through that grieving period. For the first time I had been getting on well with my mother, for the first time she praised me – without any buts.”

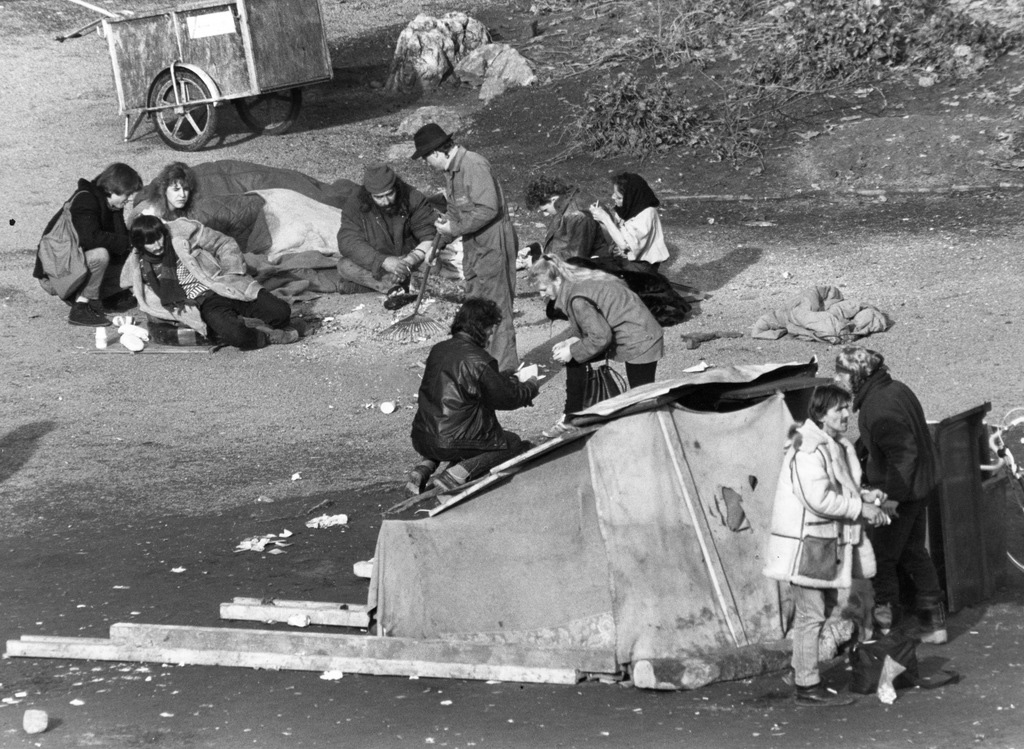

Evelyn hardly drank at that point, but she was sniffing heroin and cocaine. Eventually she gave up her German literature studies, and worked in a bookshop, first in Bern, then in Zurich. It was there that the Platzspitz, Europe’s biggest open drug scene, had just been cleared.

In the meantime Evelyn had a job in a second-hand book shop at the station in Zurich. “The shop ran just fine, but it meant a lot of stress. In my breaks I had to get more stuff, because I was heavily addicted to heroin, even though I was not injecting at that stage,” she points out.

More

‘The heroin programme is a kind of prestige project’

Total collapse

She spent more and more of her time at the abandoned railway station in Letten, where a new drug scene had started up after the closing of Platzspitz. She hardly slept or ate, was always on the go, and late for everything.

At age 34, Evelyn started to “shoot up”. Even though she was well paid, her salary was never enough. Heroin then cost about CHF400 ($320 at the time) a gramme, almost four times what it is today.

So she began to take money from the till. Since the shop did good business, it was not noticed for a while. Then the boss called, because the take for a whole week was missing.

Her situation was finally revealed. “At last! I was relieved, but so ashamed that I hid – at the Letten yards, for three days,” she explains. “I was filthy, had no money, no job and no home.”

She was finally picked up by her sister and her father, spent a month with him under constant watch, was “good” about looking for a treatment centre and began her first official withdrawal attempt at a Bern clinic, which lasted only four days. A second attempt a short while later ended after just three days.

“Those were the days of ‘reforming’ people, because heroin was the devil’s work, and as an addict you had to suffer. This attitude was widespread among the medical profession and in society generally. Today we have moved on,” says Evelyn.

She attempted the withdrawal more for her family and for those who were worried about her. “But I wasn’t ready yet. I had to hit rock bottom first.”

She took to the streets in Solothurn, Biel, Bern and slept in homeless shelters. Evelyn calls this time her “Tour de Suisse”. To get drugs, she provided sexual services once in a while or stole from other junkies.

She had no contact with her father or her siblings during this time. But she never really felt at home on the street, in the Zurich “needle parks” at Platzspitz and Letten or in the open drug scene in the capital Bern, near the parliament buildings.

More

Revisiting a former open drugs scene

Shortly after a controlled distribution centre was opened in Bern, Evelyn was one of the first to join the heroin programme. She weighed only 45 kilograms. But since she no longer had to seek out her drug supply, she built up her strength.

She pulled herself gradually together, moved into a co-op residence and worked in various sheltered projects.

Two years later she got an apartment of her own. “I have lived here for 18 years and am so stable that it’s almost boring.” Her work situation has stabilised too and Evelyn has been an employee at a Bern cooperative restaurant for a number of years.

More

Keeping a long-term job despite addiction

Since joining the heroin programme, she has only consumed drugs a few times on the side, and no longer experiences real breakdowns. She sees her father regularly, and has contact with her siblings.

“For the first time I have a kind of relationship with my sister. And my brother has softened his attitude towards me, too,” she adds.

Evelyn has a small group of friends, reads a lot, and dreams of one day recording a CD with songs she has written. “My life is okay, I am not unhappy, I get along all right, even though I do get lonely once in a while, which is in the nature of things,” she points out.

Looking back, says Evelyn, there was a kind of inevitability about the way her life unfolded, though she might have made different decisions.

“It is what it is, it’s my life. I don’t have regrets, although I ruined a lot of things and lost a lot of friends along the way.” She is able to accept her situation and she is pleased that she is financially self-supporting and does not need social welfare.

“Heroin is a part of me, but it is important to me not to be just identified with it – although the likelihood of me eliminating it from my life is fairly low.”

In Switzerland there are 22 official heroin distribution centres, 21 in German-speaking Switzerland and one in Geneva. Two are inside prisons.

When heroin-assisted treatment was introduced in 1994, just 400 people signed up. Two years later the programme had 1,000 addicts on the books, and over the past ten years the numbers have remained stable at around 1,500 (in 2012, it was 1,578, of which 391 were women).

In 1994, 77.5% of heroin recipients were under 35. In 2011 only 17.4% were under 35. In 2012 the average age was 42.2. The age range is between 20 and 75.

Since 2005 there have been 100 to 150 new cases per year. In 2012, the average age of new entrants to the heroin programme was slightly over 37.

50% of heroin patients remain at least two-and-a-half years in the programme and 20% for at least 15 years.

Most new entrants in the last 10 years were single (75%), while about 8% are married. The rest are separated, divorced or widowed. The proportion of women is 20-25%.

The proportion of non-Swiss heroin recipients rose from 12% in 2000 to 18% in 2011. The proportion of non-Swiss citizens in the resident population as a whole is 23%.

The proportion of HIV patients has been stable for ten years at around 10-15%.

(Source: Swiss Institute for Addiction Research)

(Translated from German by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.