How Switzerland, Scotland and Norway seized children from itinerant families

In the 20th century, children from itinerant Yenish families in Switzerland were systematically taken from their parents and placed in institutions – part of a state-backed effort to destroy their way of life. Similar practices existed in Norway and Scotland, where for decades, authorities and charity organisations targeted people with itinerant lifestyles.

Between 1926 and 1973, Swiss authorities and charity organisations forcibly took Yenish children away from their families. At the end of February 2025, the Swiss government formally recognised these actions as crimes against humanity.

Switzerland was not the only country in 20th-century Europe trying to erase nomadic cultures.

Antigypsyism – a specific form of racism toward these groups – was widespread across Europe, and systematic abuses were committed in many places. Yet the practices in Scotland, Norway and Switzerland were notably similar.

For decades, aid organisations in these three countries sought to eradicate nomadic or itinerant lifestyles by forcibly removing children from their parents – all under the guise of care, and with the backing of the state.

What Elizabeth Connelly experienced

In 1910, near the Scottish city of Perth, Elizabeth Connelly was sitting alone with her three daughters in their caravan when the “cruelty man” arrived – an inspector from the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. He took them all to his office.

Elizabeth, who could not read, was made to sign a document which, unbeknownst to her, gave consent for her daughters to be taken away. Gracie, Mary and Margaret, aged between six and ten, were taken to a children’s home, then shipped to Canada and forced to work as domestic labourers. They never saw their mother again.

Arne Paulsrud did not know his origins

In 1944, in the small Norwegian town of Tollnes, seven-year-old Arne Paulsrud was taken from his mother and placed in a children’s home. Staff at the institution told him that his mother was “unfit” and should never have had children. The two were forbidden from seeing each other.

Only as an adult, after his mother’s death, did Arne Paulsrud learn that he was Romani. She had kept it secret out of fear of the authorities.

She too had been taken away from her parents and had grown up in foster care.

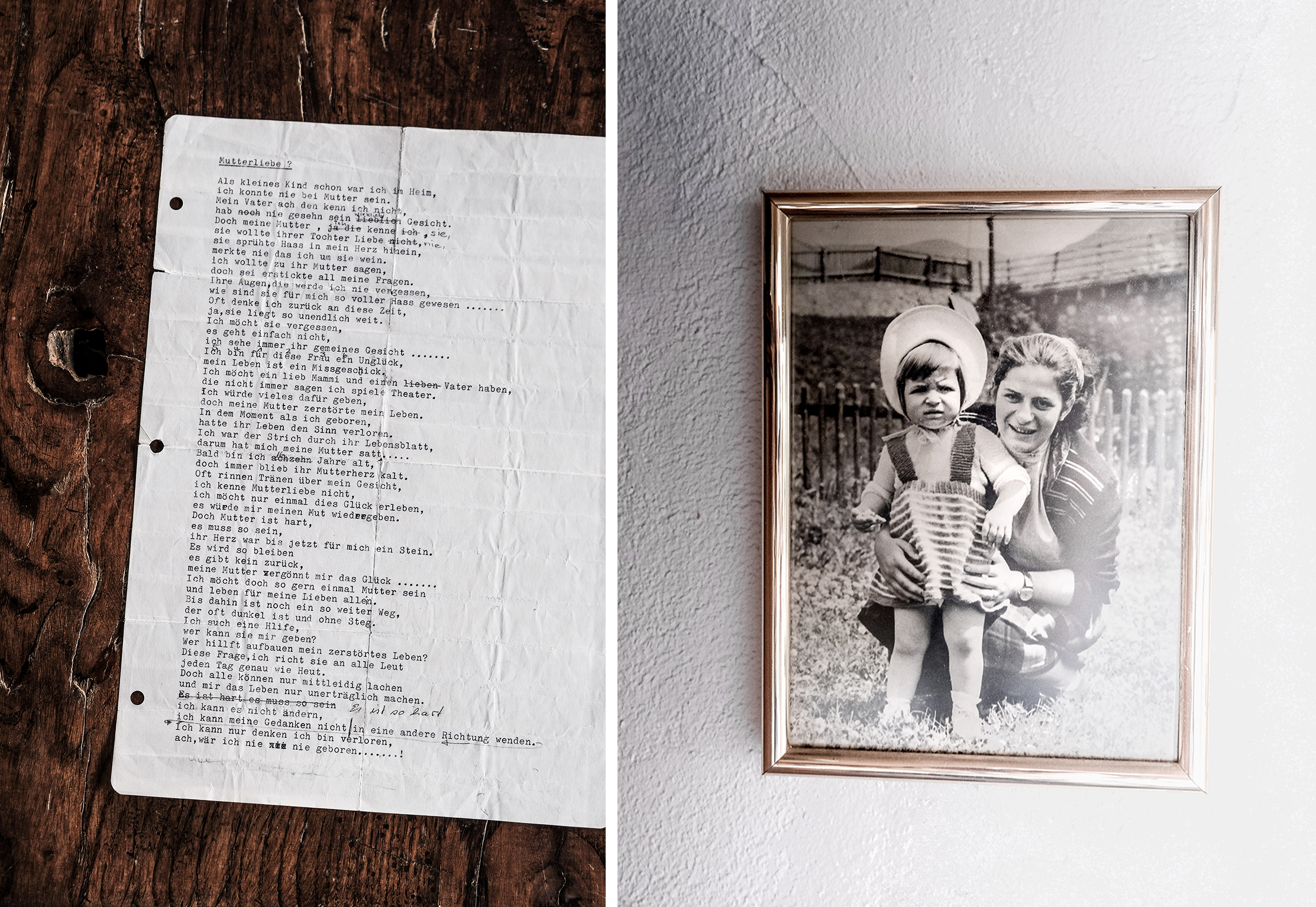

Ursula Kolleger was taken by the police as a baby

In 1952, in the Swiss village of Rüti, the police took six-month-old Ursula Kollegger and placed her in a children’s home. The aim was to separate her from her family and raise her in a “settled” lifestyle.

Throughout her childhood and adolescence, the Yenish girl was moved from one institution to another. She was never allowed to see her mother again.

An estimated 12 million Roma live in Europe today, making them the continent’s largest minority group. Despite a very heterogeneous population, they are united by their common language, Romani. While the vast majority of Roma do not lead a travelling lifestyle, they have always been regarded as a nomadic people – a perception shaped by centuries of persecution.

Roma who have lived for centuries in western and central Europe refer to themselves as Sinti. The term is particularly common in Germany. In Norway, Roma communities which have been there since the 16th century refer to themselves as Tater or Romani, distinguishing them from the Roma who came to Norway after the abolition of slavery in 1856, from what is now Romania.

Travellers and Yenish

Travellers in Scotland and Ireland call themselves Nawken or Mincéirí. They are not related to the Roma and have their own distinct language. However, like the Roma, they have long been labelled as “nomads” and subjected to similar anti-gypsy stereotypes and discrimination.

The same is true for the Yenish, who live in Switzerland, France and Germany, and who also speak their own distinct language.

Thousands of kilometres and many decades separate the experiences of Elizabeth Connelly, Arne Paulsrud and Ursula Kollegger. And yet their stories are disturbingly similar.

This is no coincidence. Since the 16th century, authorities in northern, central and western Europe have used deeply repressive practices against those who were pejoratively labelled as “gypsies” or “vagabonds.”

Banned from settling, refused citizenship, and turned away at borders, authorities chased them out under threats of drastic punishment and shuffled them around from one country to the next.

By the end of the 19th century, police in various European countries began collecting personal data on travelling communities in so-called “gypsy registers”. The Nazis later used these records to carry out the systematic persecution and genocide of Roma, Sinti, and Yenish people during the Second World War.

A decree by Empress Maria Theresa

But the destruction of a people often begins long before violence – with ideas, laws, and language, designed to erase them. In 1773, Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa issued a decree that Roma children as young as four were to be taken from their families and raised elsewhere. It is unclear how strictly these laws were enforced. But Maria Theresa’s policies laid the groundwork for ideas that would become widespread in countries like Switzerland during the 20th century.

Starting in 1926, the Swiss charity Pro Juventute set out to remove Yenish children from their families to “settle them down” and thus combat the “evil of vagrancy”. By 1973, the organisation, supported by public authorities and church organisations, had taken 600 children from their families.

Today, an estimated 2,000 people are believed to have been affected by these removals.

Read more about how for decades, Pro Juventute, a Swiss charitable foundation dedicated to supporting children and young people, systematically tore nomadic Yenish families apart:

More

How Switzerland tried to wipe out Yenish culture

In Norway, the Norsk misjon blant hjemløse (Mission Among the Homeless), founded in 1897, aimed at combating the “vagabond lifestyle” of the country’s Romani population, known as Tater.

Lillan Støen, secretary of Taternes Landsforening, the largest umbrella organisation of Norwegian Romani, told SWI swissinfo.ch: “The Mission took a third of all Tater children from their families and placed them in homes or with foster parents.” From 1900 to 1989, between 1,500 and 2,000 children were taken away from their parents.

Romani were to be re-educated in Svanviken

In 1908, the Norwegian organisation also founded the Svanviken labour colony. Roma were to be re-educated there and live a “settled life.” They had to follow strict rules with stringent daily routines and stay in the colony for at least five years. “If you didn’t obey, your children could be taken away from you,” says Støen.

Travellers in Scotland faced similar programmes aimed at forced assimilation. Under the Children Act, passed by the British parliament in 1908, charities and other institutions were allowed to remove children from their homes if they spent fewer than 250 days a year in school. In the years that followed, the Scottish Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Children followed a similar practice to that of Pro Juventute and the Mission to the Homeless.

Children like Elizabeth Connelly’s three daughters were forcibly taken from their families, and in some cases shipped overseas. “It was cheaper to hire them out in the colonies than to send them to school in Scotland,” explains Elizabeth Connelly’s great-granddaughter, Dr Lynne Tammi-Connelly.

Today, Tammi-Connelly is among the most prominent traveller activists in Scotland and has been campaigning for years to bring public attention to this dark chapter of the country’s history.

Concepts from the doctrine of race

Behind this policy of child removal lay a body of thought based on racist and now-discredited eugenic ideas. In Switzerland, Chur psychiatrist Johann Joseph Jörger believed that “vagrancy” was a “dangerous hereditary disease”. Starting in 1905, he compiled lists of names and family trees of Yenish families – using data supplied by Pro Juventute.

In Norway, Roma women were forced or coerced into sterilisation, especially at the Svanviken work colony, because it was believed that the “vagabond lifestyle” was hereditary.

In 1938, Scotland welcomed Nazi eugenicist Wolfgang Abel, who conducted pseudoscientific measurements on Travellers for his “racial surveys”.

Even decades after up to 500,000 Roma and Sinti were murdered by the Nazis during the Second World War, little was done to change the way nomadic or itinerant communities were treated.

How did the policy of persecution finally come to an end?

After 1945, in many communist countries of Eastern Europe such as Poland and Czechoslovakia, Roma were forced into newly established ghettos. Those who resisted faced the threat of losing their children or being jailed.

In Czechoslovakia, starting in 1966, Roma women were sterilised without their consent or under coercion – a practice that continued until the 2000s. Across much of Europe, officials continued to enforce policies of cultural assimilation, restricted travel by caravan, and closed transit sites which could be used for short-term stays.

In Switzerland, the forced removal of children continued until 1973. In Scotland, from 1940 to 1980, Traveller communities were forced into dilapidated settlements. And in Norway, the Svanviken labour colony remained in use until 1988.

Public protest in these countries first began to emerge in the 1970s, driven in part by investigative journalism and documentary films. Above all, it was Roma, Sinti, Yenish, Romani and Travellers who became politically organised and advocated for their rights.

Still, it would take decades before governments finally acknowledged the injustice that had been done.

What is your opinion? Join the debate:

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl, adapted from German by David Kelso Kaufher/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.