Climate refugees left in legal limbo

“Climate refugees” are not recognised by international law. Should a new status be created to protect them? Opinions are divided, even as more and more people are forced to flee their homes because of the effects of climate change.

In 2009 the Maldivian government held a symbolic underwater meeting to raise global awareness about the existential threat posed by rising sea levels to their low-lying island nation. Images of government ministers, clad in scuba gear and gathered around a table six metres below the surface of the ocean, were beamed around the world.

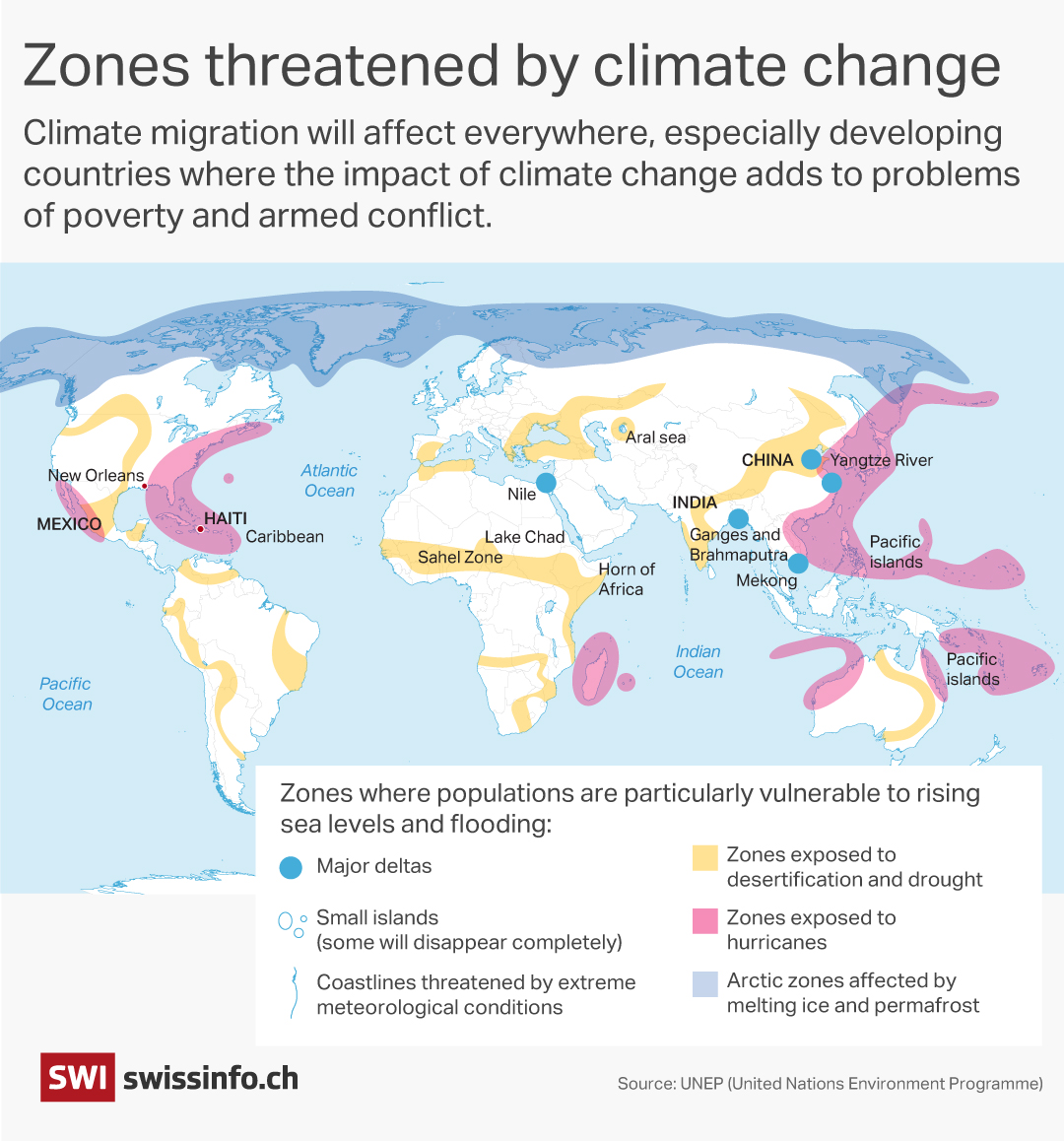

Rising sea levels, drought, floods, landslides, wildfires – climate-induced natural disasters have driven more than 220 million people from their homesExternal link in the past ten years, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Those affected often fall between the cracks of international law, and many are left without due legal protection.

The 1951 UN Refugee Convention does not recognise climate change and its effects as a basis for seeking asylum.

The former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and climate change voiced his preoccupation about this at a briefing in Geneva in 2022: “I am particularly concerned about this issue of people displaced across international borders that are not defined as refugees under the Refugee Convention and therefore fall through the cracks as far as legal protection is concerned.”

This significant gap in the law is all the more worrying at a time when nearly half the world’s population lives in environments that are “highly vulnerable” to climate change, according to estimates by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Landmark UN opinion

“The effects of climate change […] may expose individuals to a violation of their rights under articles 6 or 7 of the Covenant, thereby triggering the non-refoulement obligations of […] States,” reads the historic decision. “Furthermore, given that the risk of an entire country becoming submerged under water is such an extreme risk, the conditions of life in such a country may become incompatible with the right to life with dignity before the risk is realized.”

While this precedent opens a door, the admissibility criteria remain strict. The applicant, Ioane Teitiota, was sent back to his country, as he could not demonstrate that he was facing an “imminent” danger.

Divisive issue

Five years on, the international community remains divided over the creation of a specific status for climate refugees, and talks on the issue have run aground.

More

A ‘crucial moment’ for climate justice is unfolding in The Hague

“It’s very rare for someone to cross a border solely because of the climate. Many people affected by global warming are actually stuck where they are because they don’t have the resources to leave,” Etienne Piguet, a geographer specialising in climate migration at the University of Neuchâtel, told GéopolitisExternal link, a programme on Swiss public television, RTS.

In his opinion, defining who is a climate refugee is all the more difficult because these displacements, which are often temporary, have many causes. “In most cases there are multiple factors. The climate is often the final straw,” he said.

In Geneva, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) is focusing above all on action to help people prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change. “Modifying the legal framework can take time and prove ineffective for most climate-displaced people, most of whom are displaced within their own countries,” Rania Sharshr, director of climate action at IOM, told SWI swissinfo.ch. The IOM estimates that more than 80% of climate-induced displacement occurs within countries.

“We believe it is more important to enable people to keep living in their own countries, for instance by improving access to water or helping protect agricultural land,” she added, citing the example of dyke building in Yemen to protect flood-prone farmland.

Climate-induced migration is not limited to developing countries. “Today, we are seeing similar cases in France, Switzerland and the United Kingdom,” says Etienne Piguet.

In France’s Pas-de-Calais region, recurrent flooding has led to the relocation of an entire village. The old village is to be destroyed and the land declared unbuildable as part of a flood expansion area. In Switzerland, the village of Brienz had to be evacuated in 2023 because of the threat of a rockslide.

“Maybe we used to think that the Global North was immune to this, but this is no longer the case. While we are better equipped financially to adapt, we are by no means spared.”

“We won’t be able to build dykes everywhere,” Piguet cautions. “Technology can provide solutions, but it won’t be enough. We absolutely have to combat global warming, while assisting those who are already affected.”

In his view, grassroots efforts will have to go hand in hand with greater international solidarity. “The international community should set up funds to meet the challenges ahead,” he said.

The UNHCR has launched a fundExternal link to boost the protection of refugees and displaced communities who are most threatened by climate change. The aim is to equip them to prepare for, withstand and recover from climate-related shocks. The agency hopes to raise $100 million (CHF82 million) by the end of the year.

First steps towards climate visas

For some, however, fleeing is the only option. “For those who have no choice but to leave, for example because of rising sea levels, IOM is working with governments and communities to guarantee legal migration pathways,” Sharshr said.

Some groundbreaking initiatives are also starting to emerge, as in Tuvalu. In 2023, this small island nation in the Pacific Ocean signed an unprecedented treaty with Australia. The agreement guarantees the 11,000 Tuvaluan citizens access to visas to live, work and gradually settle in Australia. The first visas are expected to be issued this summer to 280 Tuvaluans.

More

Bangladesh sheds light on climate change migration patterns

In return, Canberra will have a say over any security arrangements that Tuvalu may want to conclude with other countries. This has given rise to heated debate on the question of Tuvalu’s sovereignty.

Gradual progress is thus being made, but it could be jeopardised by recent US government budget cuts, which target climate and environmental justice projects in particular. IOM is especially badly hit and has had to reduce its workforce, including slashing at least 20% of jobs at its Geneva headquarters. The cause of climate refugees is thus in danger of falling even more by the wayside.

Sharshr, however, is convinced that the system is resilient and can withstand these cuts. “Climate displacement will never be forgotten. It is a reality that we are facing on a daily basis, in all the countries where we work. We will continue to rally the necessary support to help people affected by the climate crisis.”

The question of the status of climate refugees is not a new issue. In 2010, Switzerland and Norway launched a consultative process with the aim of protecting people displaced across borders as a result of disasters and climate change. Five years later the project, known as the Nansen Initiative, gave rise to the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD), which was endorsed by more than 100 states in Geneva. The platform is still active and strives to push the issue forward within the different international negotiating bodies.

Interested in International Geneva? Listen to the latest episode of our Inside Geneva podcast.

Edited by Virginie Mangin. Adapted from French by Julia Bassam/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.