New detailed Swiss avalanche danger scale helps assess risks

After weeks of warm weather and bare slopes, large parts of the Swiss Alps have seen heavy snow in the past few days, especially at higher altitudes. Avalanche risks have also increased. This winter the national avalanche warning service has started issuing more precise information on danger levels in the mountains to help predict the threats.

“Medium-sized and, in isolated cases, large natural avalanches are possible as the day progresses. Even single winter sport participants can release avalanches easily, including dangerously large ones”: the message is clear from the national avalanche bulletin published on Sunday evening by the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in DavosExternal link.

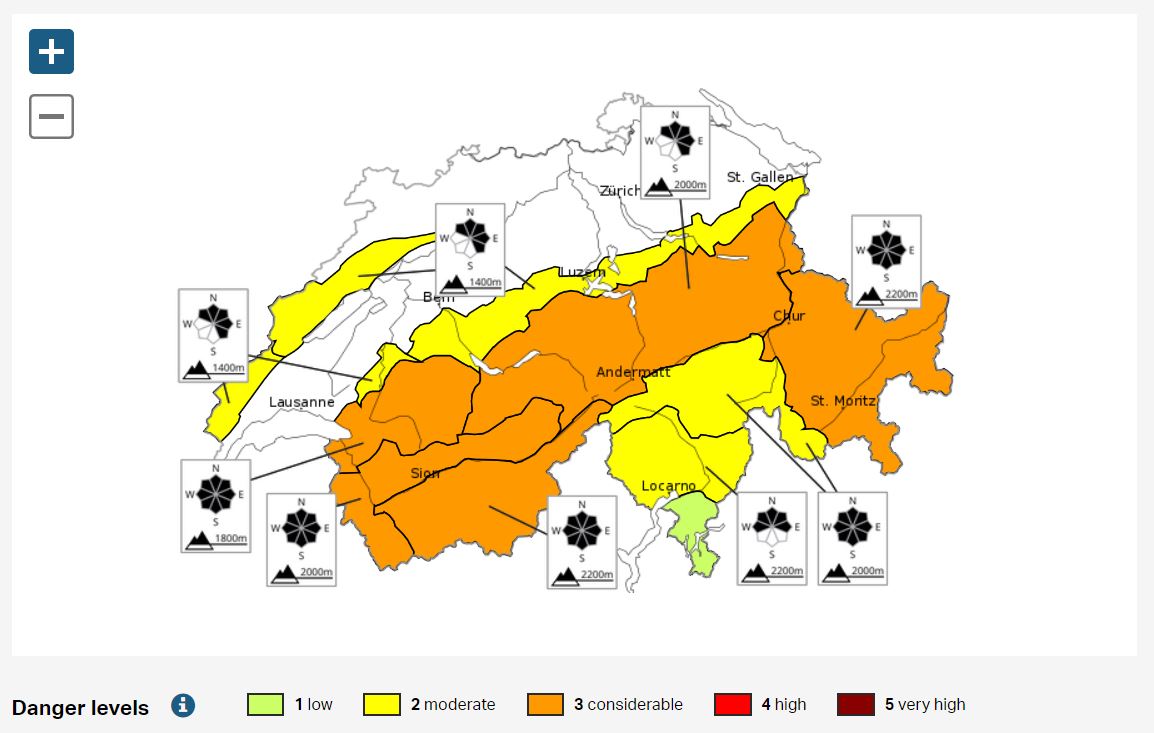

A wide orange band stretches across the SLF’s map of Switzerland. The avalanche danger level for much of the Swiss Alps is “considerable”, it declared.

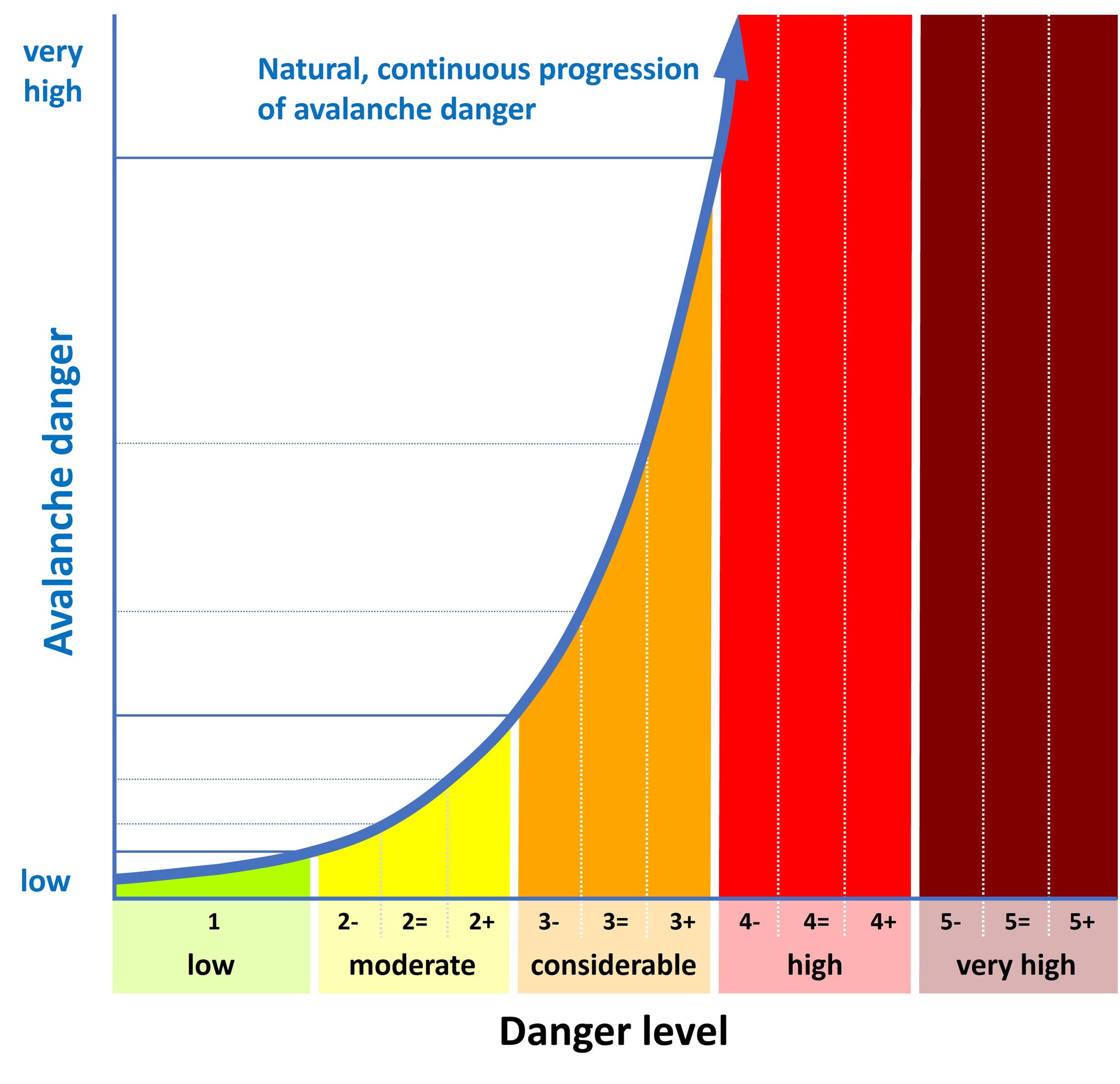

The SLF still uses the standard five-level European avalanche danger scaleExternal link to indicate the extent of possible threats in the mountains. But starting this winter, it has introducedExternal link a much more precise system, adding three sub-divisions of danger to each level.

On Sunday, the danger was assessed to be 3= on a scale from one (low) to five (very high).

But what does 3= mean exactly?

SLF says the current five levels remain unchanged. But the new subdivisions help to indicate if the danger is towards the bottom end (‑), the middle (=) or the top end (+) of a forecast level, a nuance that can more precisely reflect the continuously variable dangers as weather and snow conditions change.

Since 1945, the national avalanche warning service, run by the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in DavosExternal link, produces a twice-daily national avalanche bulletinExternal link using data gathered by 200 people trained to do the job and 170 automatic measuring stations dotted across the Swiss Alps. This information is shared and used by the police, cantons, communes, mountain resorts, rescue services and other winter professionals across the country.

If visitors to the Alps are concerned about potential snow and avalanche risks, they should check with their tour operator or local tourism office. Additional up-to-date information on avalanches and weather can be found at the following websites: SFLExternal link, SRF MeteoExternal link and MeteoSuisseExternal link.

The Davos-based institute says the new scale is a response to requests from avalanche forecasters who have wanted to pinpoint dangers with greater precision for some time.

“It’s a trick that Switzerland is the first to introduce,” says Pierre Huguenin, head of snow avalanches and prevention at SLF’s office in Sion, canton Valais.

He explains how a 3+ danger level following a heavy snowfall may evolve. “After a few days, we can show the public relatively clearly that the snow is stabilising and moving to 3=, then to 3-.”

More

What’s the real risk from avalanches?

This distinction is all the more important at level 3, a critical level especially for off-piste skiing. In the Swiss Alps this level is observed one in every three days in winter and is responsible for half of all annual avalanche deaths.

“We can clearly see the full range possible for level 3,” says Huguenin. “The higher up the scale you go, the more serious the avalanches will be.”

Over the past 20 yearsExternal link, there has been an average of 100 reported avalanches per year involving people in Switzerland. On average, 23 people die in avalanches annually, the majority (+90%) in open mountainous areas involving off-piste skiing, snowboarding, or backcountry touring on skis or snowshoes. In controlled areas (roads, railways, communities and secured ski runs) the 15-year annual average number of victims dropped from 15 at the end of the 1940s to less than one in 2010. The last time anyone died in a building hit by an avalanche was in 1999.

More

Why the Swiss are experts at predicting avalanches

Impact for skiers

“For skiers, this [new scale] is interesting information,” snow expert Robert Bolognesi told RTS public television. “With a risk of 3, you can say to yourself that you should really limit where you go, and perhaps you shouldn’t even leave the marked slopes.”

In Switzerland off-piste skiing is not illegal. Ski runs and off-piste zones are both part of the public domain. But reckless acts like ignoring warning signs and then setting off an avalanche that hits a marked run can lead to prosecution, even if there are no victims.

If a skier goes off piste and sets off an avalanche, they may be held legally accountable, especially if it buries someone, said Bolognesi.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if in the future, judges took this new precision on the avalanche scale into account,” he said.

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.