Space, the final frontier of sustainable investment

Space is no longer the preserve of states. Private operators are everywhere. In a recently published book, former banker Raphael Röttgen argues space is the new frontier for investors — as long as they are passionate, have the right connections, and sufficiently deep pockets.

$46 billion (CHF41 billion): that is the estimated value of SpaceX, the company owned by Elon Musk, which now transports astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) and which has already raised $5.5 billion through investment funds.

Another large private space company, Blue Origin may be more discreet but nonetheless receives $1 billion annually from its founder Jeff Bezos. And he can afford it: the head of Amazon is believed to be the richest man in the world.

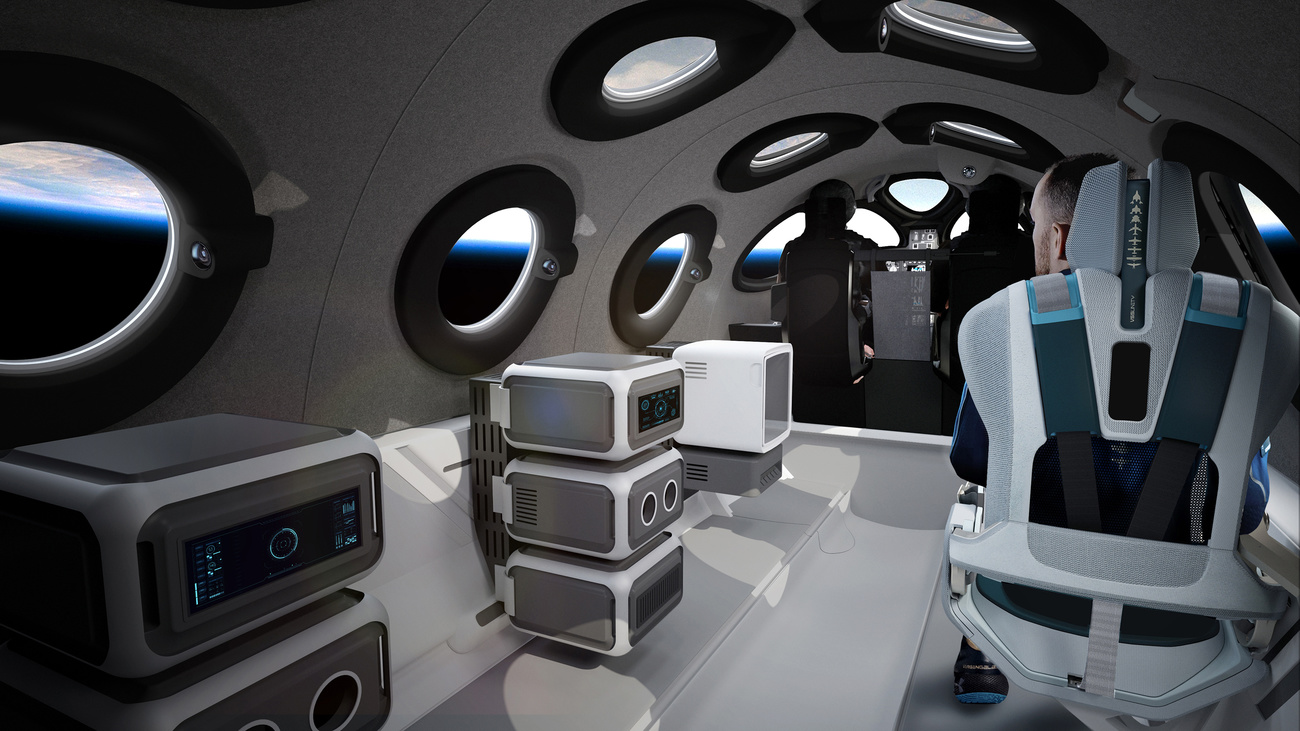

Founded by billionaire Richard Branson, Virgin Galactic promises to send the first tourists into suborbital flight soon, and has received large financing from sovereign investment funds based in the United Arab Emirates.

These three major players are far from being the only ones. Over the last decade, space businesses have been sprouting like mushrooms. In 2009, the total funds raised by these kinds of companies barely reached $1 billion. By 2019, it had reached $6 billion. More than half of this money went towards three types of activities: satellite communications, observation of the Earth, and building rockets.

From finance to space

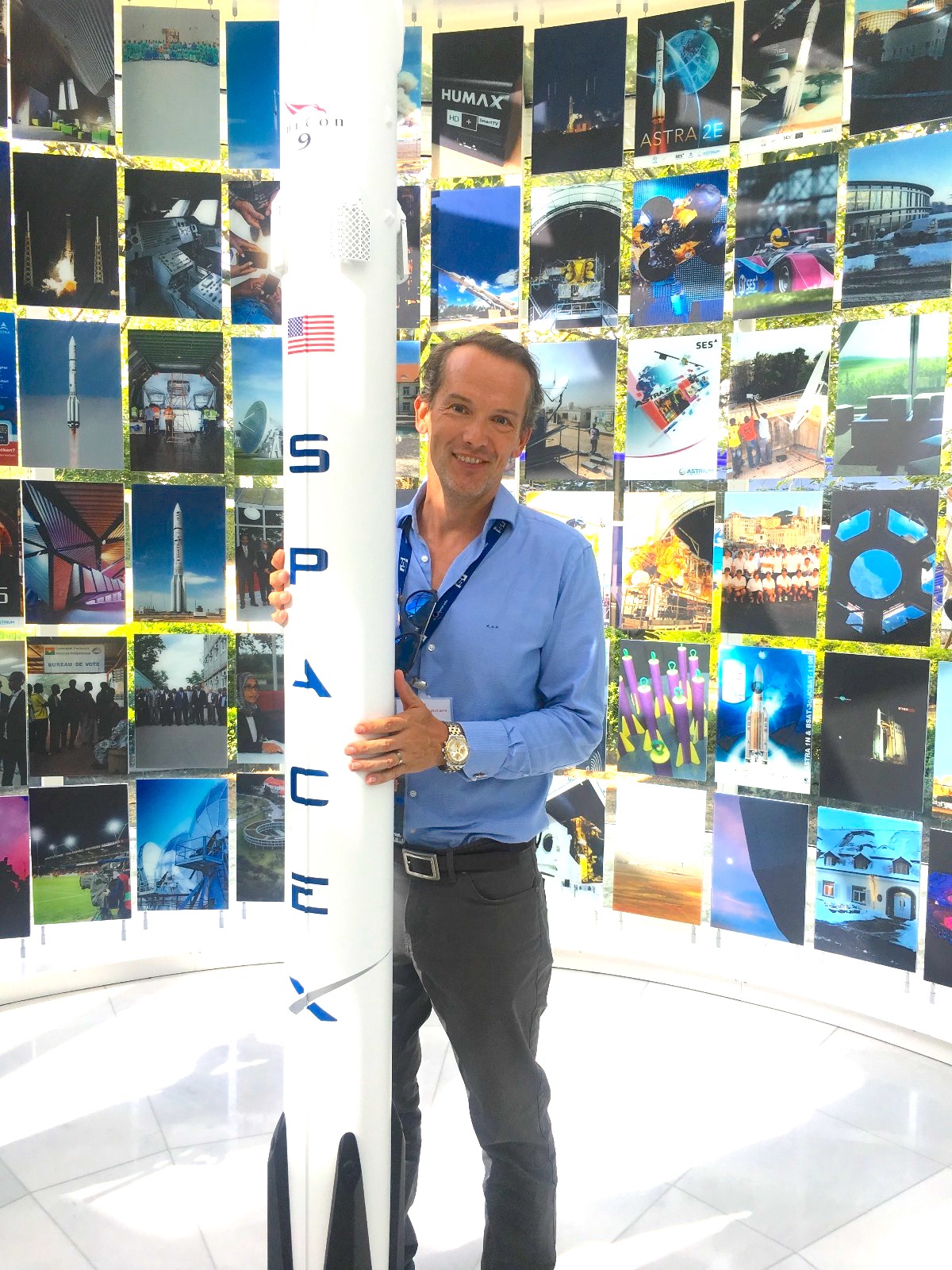

These figures are provided by Raphael Röttgen in his book Hoch Hinaus (flying high), which is hot off the presses. With two decades of experience in finance, the German based on Zurich’s so-called gold coast believes space is a future field of action for investors.

However, Röttgen’s intention was not to write a manual for them “which would end up on the specialised shelves of bookstores. The people who want to invest will find something in if for them, but those who want to work in space, and all those who simply want to watch, understand and wonder, should also find something of interest.”

Over 236 pages, the book offers a vast panorama of space exploration, from the first rockets to the faraway dreams of colonising the Moon or Mars.

In 2017, Röttgen left banking (notably he worked for JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank) and completed a diploma in space studies at the International Space University of Strasbourg. At the beginning of this year, he founded E2MC, a consultancy business for investors in the space sector. It aims to create bridges to make the sector more accessible to investors.

That’s because these businesses are mostly start-ups, and none of them (apart from Virgin Galactic) is listed on the stock exchange.

“If you want to invest, you have to answer the calls for funds, or personally know one of the company managers. And the amounts have to be substantial, nothing less than tens of thousands of francs,” says Röttgen. Suffice to say, space is (still) not a field of play for Sunday punters.

Rocket boom

In the meantime, it is already very present in our lives and has been for a long time and more that most people realise; from simple telecommunications, to GPS (and other positioning systems), or the surveillance of our planet (for weather, agriculture, pollution and any number of other areas).

One sector which is booming is rockets. The time when the national space agencies were supplied exclusively by the giants of the military industrial complex is long gone. Arianespace, then SpaceX and Blue Origin have broken those monopolies. Last year, Israel was supposed to become the fourth nation to land on the Moon. And even though Beresheet probe crash landed, it was nonetheless the first craft to reach another world that was almost entirely privately funded.

The stakes are clear: it is about lowering the price per kilo of payload wrested from the earth’s pull, which is currently tens of thousands of dollars. Innovations like Falcon 9 from Space X, the first reusable rocket, should contribute to that greatly.

Love of risk

But before achieving this feat, Elon Musk’s business also had its fair share of accidents. Launching a rocket is never a routine operation; nor does investing in space come without risk. In Switzerland, it is hard to forget the collapse of Swiss Space Systems, the start-up from Vaud which claimed to cut the price of sending small satellites into orbit but whose entire business plan was based on excessive optimism — not to mention a large amount of bluff.

“Investing in the frontiers of technology is always a risk. But it could pay off over the long term. Simply think of the first to launch internet companies,” comments Röttgen.

And the risk of a bubble? Of course, it exists, as it does with everything that is new. But space is also paradoxically a sector that is more traditional in that it consists of building machines. And state guarantees are solid.

“It is interesting to note that Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos both started by making a fortune with the internet before launching into industrial activities,” Röttgen comments.

And then, unless you bet on the exploitation of water on the Moon for future colonies or missions to Mars, the return on investment is not necessarily that far off.

“For example, if you choose a business which manages data sent by satellites, the profit could be rapid,” says Röttgen.

Sustainable

The enthusiasm, in any case, is definitely there. A long-haul traveller (his company has offices in Zug, Florida and Brazil), Röttgen says he encounters it everywhere.

“Space is a dream, the prospects are very exciting, the potential is enormous, it is the new frontier,” he says. The idealism of the former finance professional is palpable.

“Those who have already been often speak of the ‘overview effect’. Seen from space, the Earth is without borders, it is a lesson for our politicians, who should go for a spin in orbit — perhaps it will come with space tourism. More seriously, I see in space a uniting force for humanity,” Röttgen says.

Röttgen recognises that his is a rather optimistic vision, although he does not rule out the possibility of sinister developments. For example, an arms race in space, or the when the day comes for protecting trade routes to the Moon or asteroids, whose mineral resources have already stirred excitement. But that prospect is still a way off.

Until then, will space become the ultimate area for sustainable investment? Röttgen sincerely believes in its positive impact.

“If you take areas like Earth observation, which serves to understand climate change or optimise agricultural planning, or the production of new drugs in microgravity, I would say that it goes in exactly the direction of the sustainable development objectives of the United Nations,” he says.

“Space is waiting for the new Greta Thunberg,” writes Raphael Röttgen in the chapter dedicated to the rubbish tip that the Earth’s orbit has become, filled as it is with thousands of objects of different sizes, each of which could have the impact of a bomb as they are launched at 20 times the speed of a rifle bullet.

The astronauts are aware of this, as are satellite operators. It is therefore not unusual for them to make a small correction in the trajectory to avoid collision, as the Swiss space telescope CHEOPS was forced to do in early November.

A Swiss start-up wants to attack the problem: Clearspace, from Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), has succeeded in convincing the European Space Agency of the importance of its project and has received €86m to develop it. Planned for 2025, the first “concierge of space” will be a satellite capable of catching wrecks in space and flipping them off their orbit so that they burn up upon re-entering the atmosphere.

If successful, Clearspace will join the flagships of the Swiss space industry, which already includes more than 100 companies of various sizes.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!