Switzerland has to ‘go above and beyond’ to implement sanctions

The war in Ukraine should be a turning point for Switzerland to change its mindset around transparency, says financial crime and sanctions expert Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at RUSI, the world’s oldest defence and security think-tank.

Switzerland has adopted 11 sanctions packages in step with the European Union since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, but how well it’s implementing sanctions is highly disputed.

Switzerland has frozen CHF 7.5 billion ($8.1 billion) in Russian assets, which the US Ambassador in Bern, Scott Miller, claimed in March 2023, without providing details, was only a fraction of what could be blocked. A few weeks later, the G7 ambassadors in Bern sent a letter to the Swiss government, criticising loopholes in the Swiss system that make it possible to evade sanctions. The Swiss government has continued to deflect the criticism and defend its sanctions record.

Sanctions and financial crime expert, Tom Keatinge, from the UK security think-tank, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), offers thoughts on how Switzerland can persuade the world that it’s implementing sanctions.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Switzerland has been heavily criticised by the United States and other G7 countries that it isn’t doing enough to enforce sanctions. Do you agree?

Tom Keatinge (T.K.): Switzerland is in an interesting position. It is a jurisdiction that will remain guilty in the eyes of the world until a generation has passed. So, I think Switzerland has to go above and beyond to persuade people that it is on the side of the good guys and prove its innocence.

Switzerland has been under pressure from the G7, but the country is also in a difficult position to some extent because it’s a taker of decisions in Brussels. In other words, it’s not sitting around the table in Brussels, but constitutionally it has decided it will implement whatever is decided in Brussels when it comes to sanctions. That inevitably leads to a disconnect as it may end up having to implement measures with which it does not agree.

SWI: The Swiss government has admitted that identifying beneficial owners of companies is a huge challenge in sanctions enforcement. There’s now talk of creating a central register of beneficial owners. Would this help?

T.K.: Without a transparent company register your ability to implement sanctions effectively is significantly reduced. How can a country claim there isn’t a connection between a sanctioned person and a company operating in their jurisdiction if they don’t have all the information at their disposal? Journalists will quickly uncover that there is a link – this is a valuable service the media industry has played for a number of years.

I think a good company register, to quote a colleague in Latvia, is the “lifeboat that you rely on if you want to have confidence in sanctions implementation”. If you don’t have a decent company register, then you’re not going to persuade people that you’re not guilty. We can debate whether they should be publicly accessible or not, but if the authorities can’t access the necessary information, then they can’t be doing their best to implement sanctions.

More

Despite criticism, the Swiss say they’re model enforcers of Russia sanctions

SWI: Why do you think Switzerland has been slow to increase transparency on the ultimate owners of companies?

T.K.: Switzerland went through its anti-money laundering evaluation by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) a long time ago, even before the Panama Papers. In the time since 2016, higher standards have been introduced by the FATF. The result is that a country that was evaluated last year will be held to a higher standard than Switzerland.

Switzerland will face a big test when it is evaluated again in the coming years. What does Switzerland do between now and then to ensure it has raised its standards in line with FATF expectations? At that moment, Switzerland will no longer be able to stand there and say, we did quite well in our report ten years ago. I think Switzerland should be looking forward rather than backwards.

But it’s also important to note that the FATF standard is a minimum standard. If you are the sort of country that is satisfied with meeting minimum standards, then you are going to open yourself up to suspicions of facilitating sanctions evasion.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted a series of sanctions on Russian individuals, companies and trade by the European Union, the United States and wealthy G7 nations. Switzerland has kept in line with the EU, implementing its tenth package of sanctions in March.

That has not stopped the international community — including NGOs and more recently the G7 — from criticising Switzerland for not doing enough. They particularly point the finger at the limited amount of Russian assets frozen in Switzerland and argue the Alpine nation could do a better job enforcing sanctions.

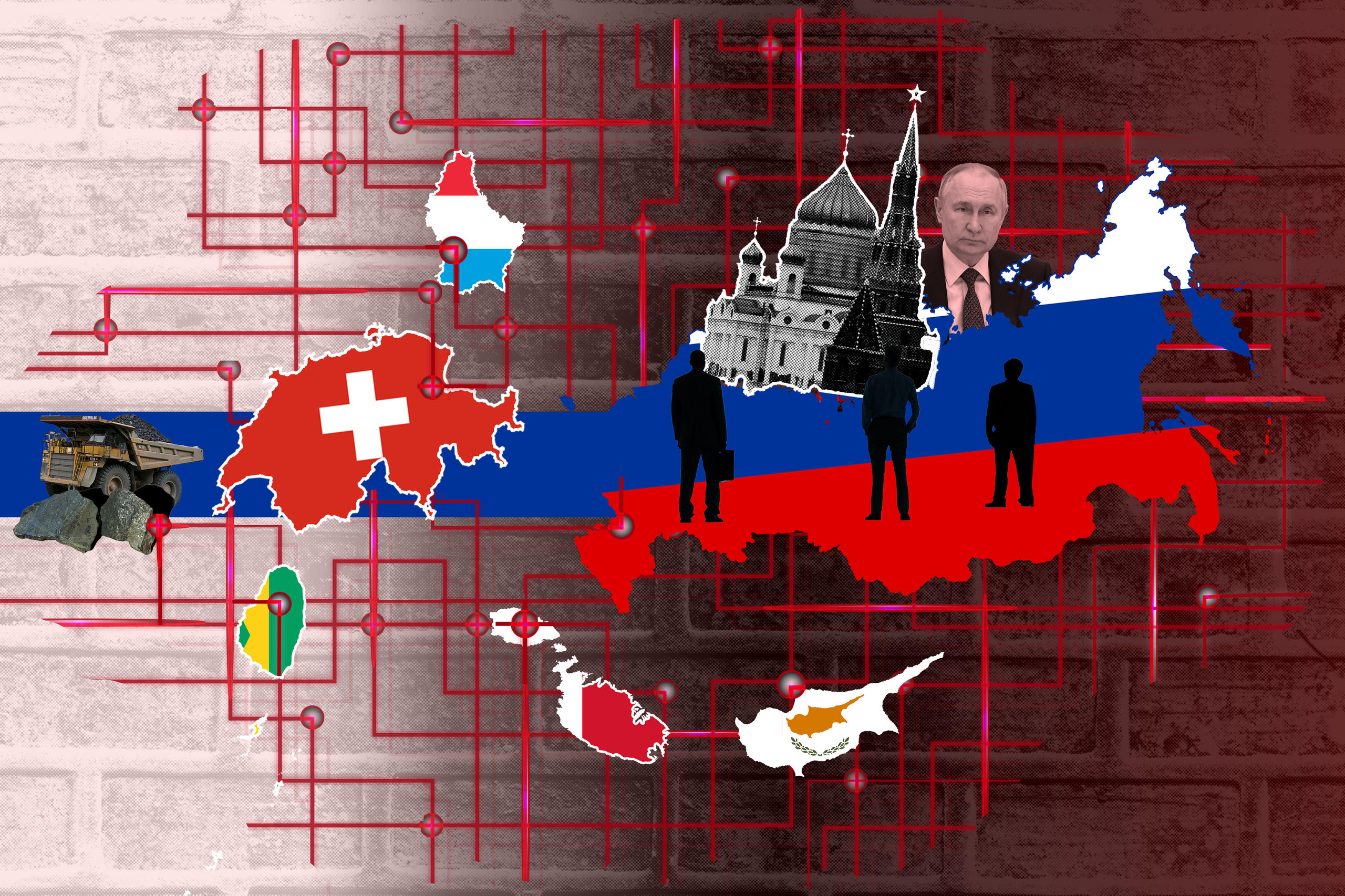

In this series we look at what steps Switzerland has taken to conform to international standards and where it lags behind. We question the grounds for sanctions and their consequences for commodity traders based in Switzerland. We also analyse Russian assets in the county and understand how some oligarchs are navigating sanctions.

SWI: Do you think the war is a turning point for Switzerland to embrace a new mindset on transparency?

T.K: Frankly, it needs to be. As mentioned, Switzerland still suffers from a secrecy reputation – rightly or wrongly – and by actively engaging with the sanctions regime, demonstrating that it is freezing assets, and leveraging national expertise (for example in commodity trading and private banking) to put pressure on the Russian economy, it will help address the remaining suspicions that surround Switzerland’s financial integrity.

SWI:Countries seem fairly aligned on sanctions but is that the same case on implementation?

T.K.: Sanctions are agreed in Brussels, but that’s just the framework. Each country has its own sanctions implementation law. The result is that there are different definitions of things like ownership and control. Most countries say that if a sanctioned person owns 50% plus one share of an entity, then it should be subject to sanctions, but the interpretation of control (where a person controls but does not own a company) differs between member states. This lack of harmonisation causes gaps that can be exploited.

More

Switzerland’s secrecy blind spot hinders sanctions enforcement

It’s also important to say that whereas banks have for a long time been very sensitive to sanctions implementation because they found themselves in trouble with US authorities, corporate Europe has had very little experience implementing sanctions. Commodity companies have had to think about sanctions a bit in the past, but not to the same extent as with Russia.

SWI:And how do you think companies are doing at implementing sanctions?

T.K.: If you talk to lawyers or consultants, they will tell you that they have clients who are still trying to continue their business, where it is not subject to sanctions. Many will argue that companies should do the “right thing”, whether sanctions are in place or not, but what’s the business case for doing the right thing?

I’ve got some sympathy for companies that say, ‘you may not like what we’re doing from an ethical or reputational perspective but we’re operating within the law. Our lawyers have signed off on what we’re doing. If you change the law, we will change how we act.’

SWI: What’s your view on the objectives policymakers have with sanctions?

T.K.: What I like to ask policymakers is – what’s your theory of change when it comes to implementing sanctions on Russia? And then, what steps do you need to take in order to make that change occur? It may be simplest to say, all trade with Russia or with intermediate countries that are selling on to Russia should go to zero. And then let’s have a conversation about allowing certain exemptions for things like medicines.

SWI: So, what do you think the theory of change should be?

T.K.: My one liner would be that Ukraine’s allies need to take action that prevents the Kremlin from funding and resourcing its military. If that’s our objective, we need to ensure sanctions on things like high-tech electronics are as watertight as possible.

But we also know that Russia has agency and so the Russian economy is shifting from a civilian economy to a military, war-footing economy. Factories that were producing buses are now producing tanks. We therefore need to think about how broad an embargo should be. That includes asking whether we should continue selling certain products to third countries that are likely to be sold on to Russia, something that is clearly happening.

SWI: But how can you enforce this?

T.K.: There are companies in Switzerland, the UK, Germany and France, which have seen sales to non-aligned third countries rise since last year. These companies should be asking themselves why these sales have jumped and if they might be linked to Russian sanctions circumvention – it is naïve to think that they are not.

We need to get the private sector to be smarter about thinking about what they are doing rather than just looking at the laws.

SWI: Switzerland has faced a lot of criticism for not joining the G7’s REPO (Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs) task force, which aims to freeze and seize Russian assets. Do you think they should join?

T.K.: If it doesn’t join, it’s doing more damage to its reputation. Why would Switzerland not join? Sceptics will think the country has something to hide.

SWI: What else should Switzerland do to persuade the world its implementing sanctions effectively?

T.K.: If I was Switzerland right now, I would find an area where Switzerland is well known and figure out how I can show global leadership on sanctions implementation on Russia in that field.

If it’s the commodity trading sector, I would be bending over backwards to work with companies like Glencore and Trafigura to help them understand the sanctions and consult them on what changes they would find helpful to achieve our theory of change.

I would be making a virtue of that. I would hold a conference on implementing Russia sanctions in commodities trading sector sponsored by Glencore and Trafigura and invite allied partners to brainstorm how we tighten this particular element of the sanctions net.

SWI: Is Switzerland doing all it can to implement sanctions?

T.K.: I should hope so, but clearly key allies think not. Switzerland should take seriously the concerns raised by the likes of the G7. For many observers, Switzerland will remain guilty until it categorically proves itself innocent.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity. Edited by Virginie Mangin.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.