Rogue losses turn screw on UBS investment bank

An estimated $2 billion (SFr1.75 billion) rogue trader loss has fuelled speculation that UBS could scale back its investment banking business more than expected.

With the scandal sparking a public and political backlash, the Swiss media is speculating that UBS may accelerate its cuts to investment banking when it announces future strategy to investors on November 17.

The bank has already been forced to abandon previously stated targets and cut 3,500 jobs to save up to SFr2 billion ($2.3 billion).

The expected $2 billion losses, that were revealed on Thursday, have virtually wiped out these savings. And the fact that an investment bank trader was responsible has hardened attitudes in Switzerland towards risky banking ventures.

“For a bank that has made mistakes in the past, this is absolutely unacceptable,” said Fulvio Pelli, president of the Radical Party, echoing the thoughts of many politicians across all Swiss political parties.

Plans scrapped

Politicians are currently debating a set of new banking regulations that would force the two big Swiss banks – UBS and Credit Suisse – to set far more money reserves aside than global competitors to cover risks.

The latest UBS debacle only looks to have hardened parliament’s resolve to clamp down on excessive trading risks that forced that state bail-out of UBS three years ago.

Since the financial crisis, UBS has scrapped its ill-fated plan to be the world’s leading investment banking operation and has resolved to pare back its business to become a support act for its core wealth management and asset management operations.

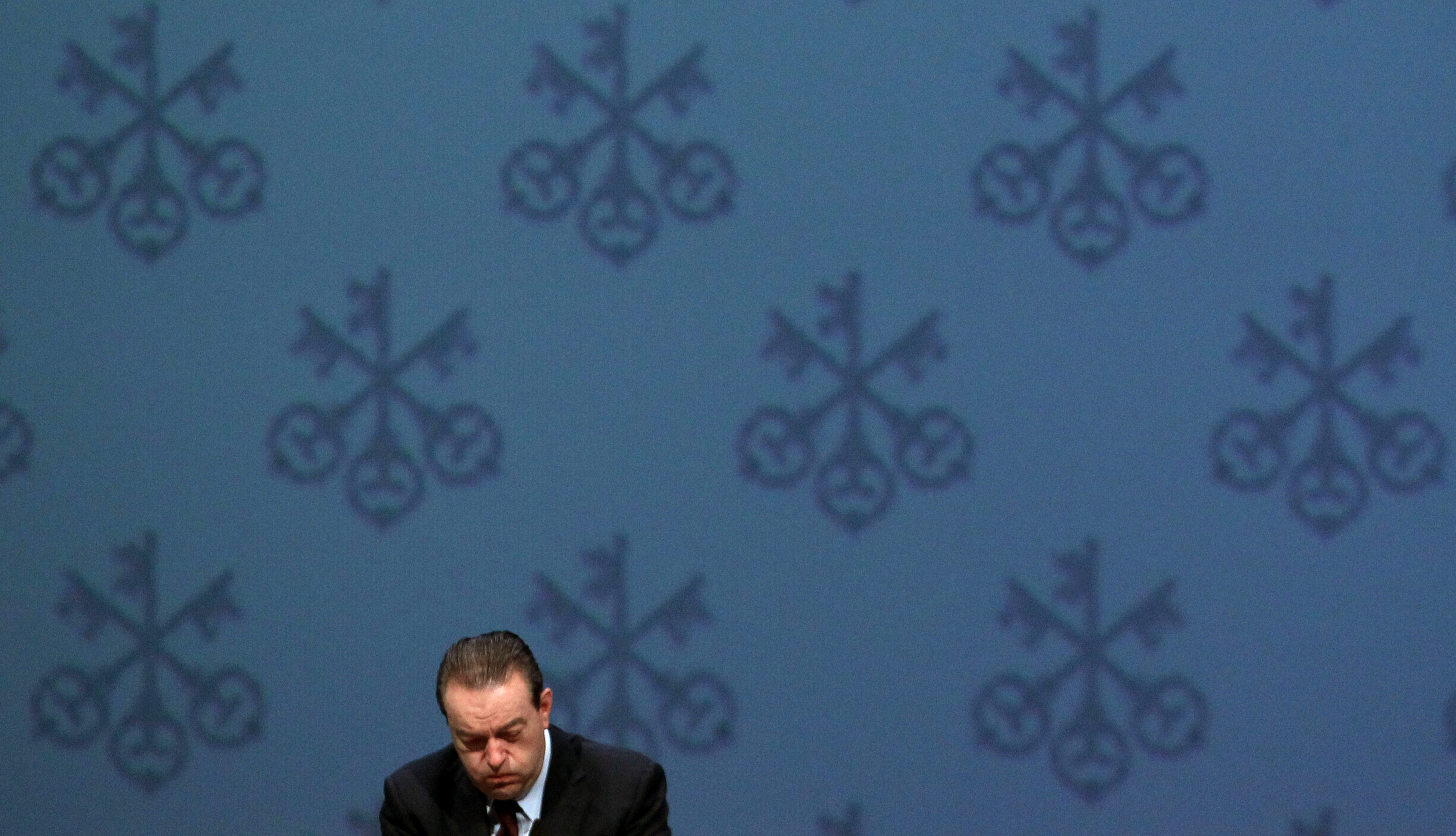

Speaking at the bank’s second quarter results conference in the summer, chief executive Oswald Grübel said investment banking could be cut back by 25 to 50 per cent to achieve this support role status.

Following Thursday’s rogue trader bombshell, analysts now expect UBS to aim for the higher end of that estimate. Some of UBS’s 17,800 investment bankers now face the prospect of losing their job, or at the very least, reduced or no bonuses.

“Delta One”

“The news is doubtless distressing and will lead to increased pressure to restructure UBS’s investment bank faster and more comprehensively,” Sarasin analyst Rainer Skierka said in a note.

Investment banking offers the prospect of spectacular profits compared with the more staid wealth management services when markets are running smoothly. But as many banks around the world found out to their cost in the financial crisis, such trades can also generate huge losses.

With markets continuing to be sluggish and risk appetite still low, investment banking profits around the globe have been disappointing so far this year. This is adding to the perception within Switzerland that domestic banks would do better to retreat from such areas and concentrate on their core private banking business.

But not all investment banking operations revolve around high risk trades, such as the so-called “Delta One” activities thought to have been carried out by the rogue trader.

Whose money?

Most of the Swiss-based investment banking operations centre around advising companies about growth strategies and merger and acquisitions. Securities trading is largely carried out in New York and London (where the rogue trader suspect was charged on Friday).

“The question now is, how big does UBS want investment banking to be to service its clients’ needs?” Andreas Venditti, Zurich Cantonal Bank analyst, told swissinfo.ch.

“It clearly needs to include the whole execution area as wealth management and asset management clients will still want to buy and sell financial instruments. On the other hand, such trading will be most exposed by tougher regulations while advisory services would be barely impacted.”

Another problem that is as yet unclear is whether the rogue trades were executed with the bank’s own money (proprietary trading) or using the assets of clients.

UBS has stated that no client positions had been affected by the rogue trades, but this might simply mean that the bank has agreed to pay for lost client money, Venditti added.

Three years ago UBS pledged to substantially cut back on its proprietary trading activities that got it into a mess in the financial crisis, in favour of trading on behalf of clients. But there is no clear distinction between the two in many cases, according to Venditti.

“The problem is that there is no clear definition of proprietary trading,” he told swissinfo.ch. “There are several stages between pure bank trading and pure client trading that constitute a grey area.”

Delta One trading appears to be one such stage, in which clients’ money is often used to strike trades with the bank pocketing profits above a set limit.

A joint investigation into the $2 billion trading losses at UBS has been opened by Britain’s Financial Services Authority (FSA) and the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (Finma).

The FSA said it would be a “comprehensive independent” probe into the events surrounding the losses.

It will be conducted by a third party firm independent of UBS, but UBS will pay for it.

Switzerland’s biggest bank was flying high in 2007, announcing record quarterly profits of SFr5.6 billion in the second quarter of that year.

This figure was achieved despite the collapse of its Dillon Read Capital Management hedge fund. However the figures hid problems that only started to come to light after the sudden departure of chief executive Peter Wuffli in July of that year.

The profits turned into a SFr726 million loss in the third quarter as the bank started writing down subprime mortgage and debt security trades. The bank eventually lost some SFr50 billion in the financial crisis.

In 2008, the situation had become so bad that the Swiss National Bank was forced to bail out UBS with a SFr6 billion loan and by taking over bad debt.

UBS also admitted to aiding and abetting US tax evaders and was forced to pay a $780 million fine in 2008. It later had to release the names of 4,450 clients to the US authorities, denting its own reputation and Swiss banking secrecy laws.

Share prices fell from a high of SFr70 in 2006 to under SFr10 in 2009.

Former Credit Suisse boss Oswald Grübel took over as CEO in 2009 with a mandate to turn UBS around. The bank was back into the black for the full year in 2010 to the tune of SFr7.2 billion.

But results have disappointed so far this year, leading to the bank cutting profit forecasts and 3,500 jobs.

On Thursday, UBS revealed that a rogue trader had cost the bank an estimated $2 billion in unauthorised trades.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.