When diagnosing a disease does more harm than good

Switzerland has the highest number of MRI scanners per person in Europe. But more screening doesn’t always lead to better health outcomes, and some experts warn that early detection can sometimes do more harm than good.

When a tsunami struck Japan in March 2011, it left 20,000 people dead and destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, triggering the worst radiation disaster since Chernobyl in 1986. Although at lower levels than the Soviet accident 25 years prior, radioactive material was released into the environment, significantly increasing the risk to the population of developing diseases such as thyroid cancer, which proliferated among children living in and around the Ukrainian city, which was then part of the Soviet Union.

Under pressure from parents, the Fukushima prefecture ordered mandatory ultrasound examinations for everyone aged 18 or under, at the time of the accident – some 380,000 people. To date, 350 cases of thyroid cancer have been detected through these screenings which have been carried out every two years since the disaster.

The incidence of cancer was 10-12 times higher than that found in other prefectures and was initially blamed on exposure to radiation. However, some experts have suggested that the excessive number of cases may be due to a combination of mass screening and the use of highly sensitive ultrasound equipment, which detected thyroid cancer at a very early stage that may not have progressed or found benign tumours that are commonly found in adults who die of other causes.

“Many unnecessary medical tests and treatments (and surgery) are being performed, which is resulting in psychological, financial, and social burdens,” says Sanae Midorikawa, a professor of clinical medicine at the Miyagi Gakuin Women’s University, some 90 kilometres north of Fukushima and one of the lead physicians examining young people in Fukushima for thyroid cancer. But she and her colleagues came to realise that while the youngsters may have been diagnosed correctly, they would never develop symptoms, let alone die from the disease.

Scanning devices and overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis, the treatment of a disease that won’t progress to cause symptoms, stems from a well-meaning intention: to detect illness early and save lives. But “our assumption that catching things early will always help hasn’t proven to be correct over time,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant neurologist at the University College London and a critic of the tendency to treat normal health variations or minor problems as diseases requiring intervention.

The proliferation of ever more powerful scanning devices might combat underdiagnosis, the failure to diagnose a disease, but it’s also fuelling overdiagnosis. Imaging for lower back pain and headaches, cancer screening, and electrocardiography in low-risk populations are processes that can easily lead to this phenomenon, according to a 2017 OECD report on wasteful spending in health servicesExternal link that’s further supported by research published in a working paper written for the Paris-based organisation in 2025.

Switzerland, home to the world’s biggest diagnostics company, Roche, and a leading manufacturer of medical equipment, is the fourth-biggest spender on healthcare as a percentage of GDP among 33 countries comprising the EU, Turkey, the UK and the four members of the European Free Trade Association, according to the trade association Medtech EuropeExternal link.

The country has the highest number of imaging devices per person among the 25 European members of the OECD, according to a January reportExternal link from the Swiss federal audit office on the appropriate usage of medical imagery. There are 80 CT scanners and MRI devices per million citizens, nearly double the number for Netherlands, although the two countries are similar in terms of life expectancy and quality of the healthcare systems.

Switzerland is also the biggest spenderExternal link on invitro diagnostics, medical tests performed on samples such as blood and urine. Although this is partly due to the cost of living, high spending on health and the quality of public health services, such as the speed at which a patient is taken into care, are also key factors, according to the Swiss Association of the Diagnostics Industry.

Yet despite heavier spending on diagnostics in wealthy nations, which leads to earlier and more frequent cancer detection, death rates from the disease remain similar to those in low-income countries, according to a 2017 New England Journal of Medicine paperExternal link cited in O’Sullivan’s book, The Age of Diagnosis, published this year.

This is because we treat cancers that aren’t necessarily going to become fatal. “We’re very good at finding diseases, but not very good at finding which will progress and which won’t,” O’Sullivan says.

Illness vs disease

It can be particularly troubling to diagnose patients without symptoms for conditions that have no cure, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Giovanni Frisoni, head of the Geneva University Hospital (HUG) Memory Center and a professor of clinical neuroscience at the University of Geneva, is part of a group which produced diagnostic criteria to limitExternal link overdiagnosis of this neurodegenerative condition.

The dominant school of thought in neuroscience posits that the presence of certain biomarkers, like tau and amyloid, is sufficient to diagnose Alzheimer’s. Frisoni and his team, however, believe that other symptoms, such as memory loss, need to be observed before coming to a definitive conclusion.

“What really matters for patients isn’t the disease but the illness,” says Frisoni, pointing to the importance of distinguishing between two phases of a condition. In the disease phase of Alzheimer’s, for example, biomarkers can be visible for 10 to 15 years before clinical signs emerge. Then, in the illness phase – which has roughly the same duration, observable symptoms such as memory loss appear alongside biomarkers. Some patients will never progress to the illness phase even though the disease is present.

“If you’re 80 years old and have a bit of amyloid, chances are, you’ll die of something other than Alzheimer’s,” says Frisoni. It isn’t helpful to tell patients with biomarkers typically linked to the condition that they have the neurodegenerative disease, he says. Instead, they should be told that they are at risk of developing it.

“It’s like cardiovascular diseases,” says Frisoni. “If you have high blood pressure, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll have a stroke, but you are at a higher risk of having one.”

His prevention protocol for high-risk patients who have yet to show memory loss include cognitive training, physical activity, networking, cardiovascular monitoring, and personalised nutritional advice. All of these activities have been shown to prevent the onset of memory loss.

Preventive screening

Preventive screening aims to detect diseases at their earliest stage—before symptoms appear or the condition progresses—enabling earlier intervention to prevent worsening or life-threatening outcomes. However, treating someone for a condition that may never cause harm can itself lead to unnecessary health risks or a deterioration in health, experts say.

For example, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test may return a positive result for prostate cancer, but the test has a high false-positive rate and most low-grade prostate cancers grow too slowly to ever cause symptoms. Yet confirming a diagnosis through physical examination is fraught with challenges. MRI scans are often inconclusive and surgical removal of the suspected tissue can lead to infections, incontinence, or impotence.

In a recent studyExternal link on the incidence of prostate cancer across 26 European countries, the International Agency for Research on Cancer found that PSA tests often leads to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. While increased testing detected far more cancers in some countries (in some cases over 20 times more), overall death rates remained similar. The authors linked this discrepancy to the screening of patients who had no symptoms, concluding that many detected cases would never have become fatal or required treatment.

For some medical conditions, preventive screening makes no difference to the outcome.

“Screening aims to improve the prognosis, but for some diseases, it doesn’t actually have any beneficial effects; it allows early diagnosis but doesn’t improve the prognosis,” says Arnaud Chiolero, epidemiologist and professor of population health at the University of Fribourg and adjunct professor at the School of Global and Population Health at McGill University in Canada.

Taking cancer as an example, Chiolero says it’s important to distinguish between various types. While screening works well for colon, breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers, it has proved not to be beneficial for ovarian or thyroid cancer, and patients would have had similar outcomes had they started treatment only once symptoms appeared.

“I’m a public health doctor, and I would be glad to say that screening is always great, but it’s so much more complex than that; only some screening (for certain types of cancer) is beneficial” says Chiolero.

More

‘Ask the right questions’

Switzerland, unlike its neighbours, doesn’t have a comprehensive preventive testing programme for breast cancer – something the Swiss cancer screening foundation is campaigning for.

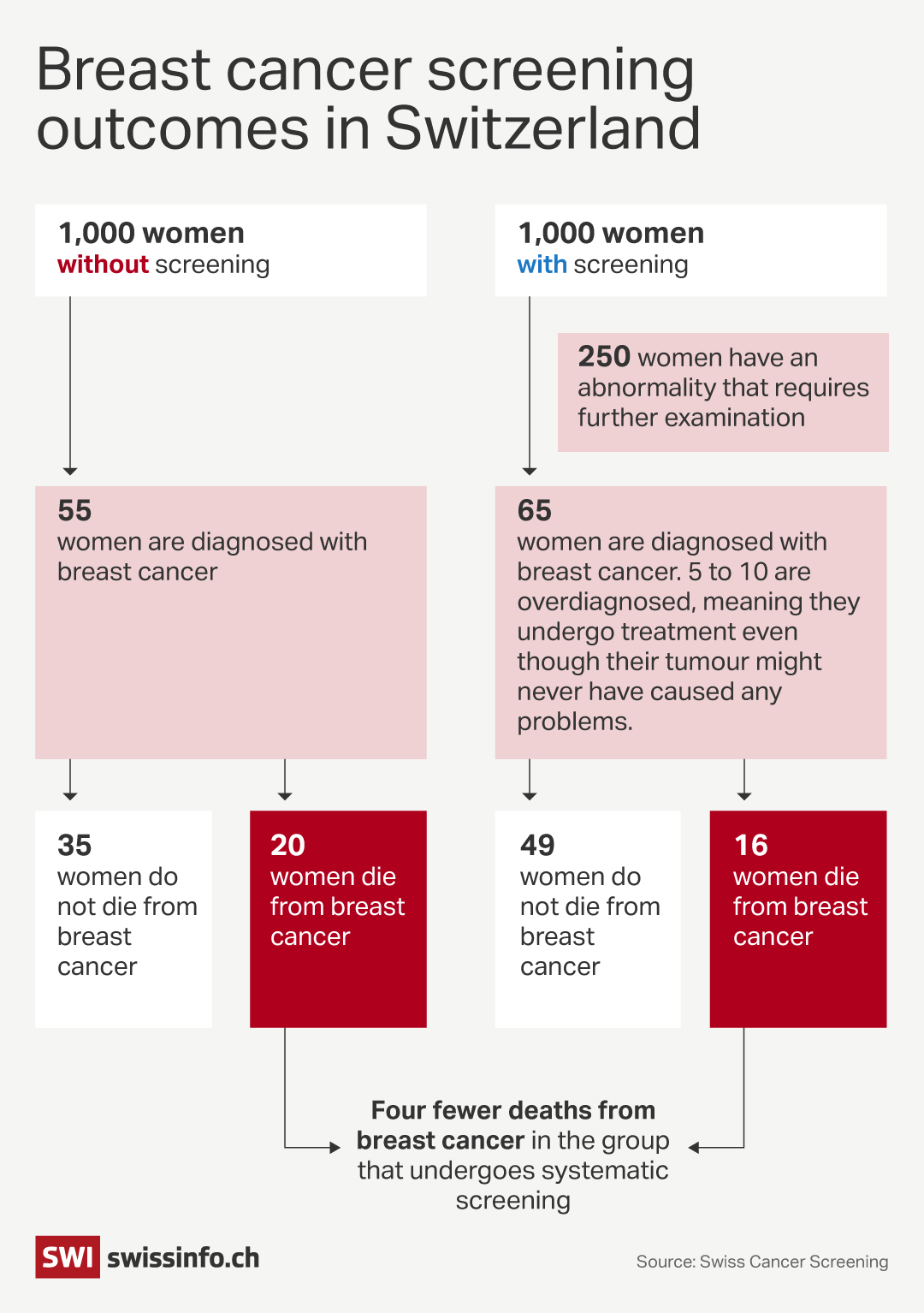

According to its dataExternal link, out of every 1,000 women enrolled in preventive screening programmes, 64 will be diagnosed with breast cancer. Of these, five to 10 will be overdiagnosed and undergo unnecessary chemotherapy, and 16 will ultimately die. For women screened only after symptoms appear, there are no cases of overdiagnosis, but the mortality rate is higher – with four additional deaths per 1,000 women compared with the preventive screening group.

Other studies confirm that breast cancer screening can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. A 2021 studyExternal link carried out in Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Slovenia found that for every breast cancer fatality averted in 1000 women screened, 0.2 to 0.5 other women were overdiagnosed and 12 to 46 were given a false-positive diagnosis.

An even earlier reviewExternal link carried out in 2012 by Cochrane, a global nonprofit network of scientists and doctors who analyse medical evidence, found limited mortality benefits and significant harm caused by early screening. The most reliable trials it reviewed showed there was no significant reduction in breast cancer deaths after 13 years of mammograms. The review estimated that for every 2,000 women screened over a decade, one breast cancer death was prevented, but 10 healthy women underwent unnecessary cancer treatment, including surgery and radiation, and more than 200 experienced many months of “important psychological distress” due to false-positive results.

“If you worry about your health and can’t live with an abnormal lump in your breast, then go ahead and have the treatment,” says O’Sullivan, who remains supportive of national screening policies despite their shortcomings. “But if you prefer knowing that you definitely don’t need an invasive treatment before you have it, you can ask to enter a watchful waiting programme,” she says, referring to the monitoring of medical problems with regular tests to avoid unnecessary treatments.

She proposes that before undergoing screening, patients should be told about the uncertainties so that they have the chance to ask the right questions beforehand and when they get a diagnosis, they can make informed choices.

“It’s about understanding the issues and knowing how you prefer to manage your own health problems,” O’Sullivan says. “A diagnosis is supposed to help you and if all it does is validate a suffering, without alleviating symptoms, leading to a treatment or improving circumstances, then we have to question whether it’s really useful.”

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.