In Switzerland, Chinese dissidents now know they are not alone

After protests in China against the government’s zero-Covid policy spilled over to Chinese communities abroad, some dissidents in Switzerland found the courage to make their voices heard for the first time – and want to continue to take a stand without fear of retaliation.

Like many Chinese living overseas, Yiyan* spent the final days of November anxiously consuming news about protests that had erupted in cities and university campuses across China. When word came that police in Shanghai had detained several demonstrators and were randomly checking commuters’ mobile phones for the presence of foreign apps, the Swiss resident could no longer sit still.

“I got really scared,” says the Chinese native. “So I got on the train and cried my eyes out all the way to Zurich.”

Through an encrypted online chat, Yiyan knew that people were planning to gather on the Rathaus Bridge in Zurich to show solidarity for protesters in China and call for political change. Propelled by fear for the people she knew in Shanghai, she was going to do something she’d never done before: take a stand over events in her homeland.

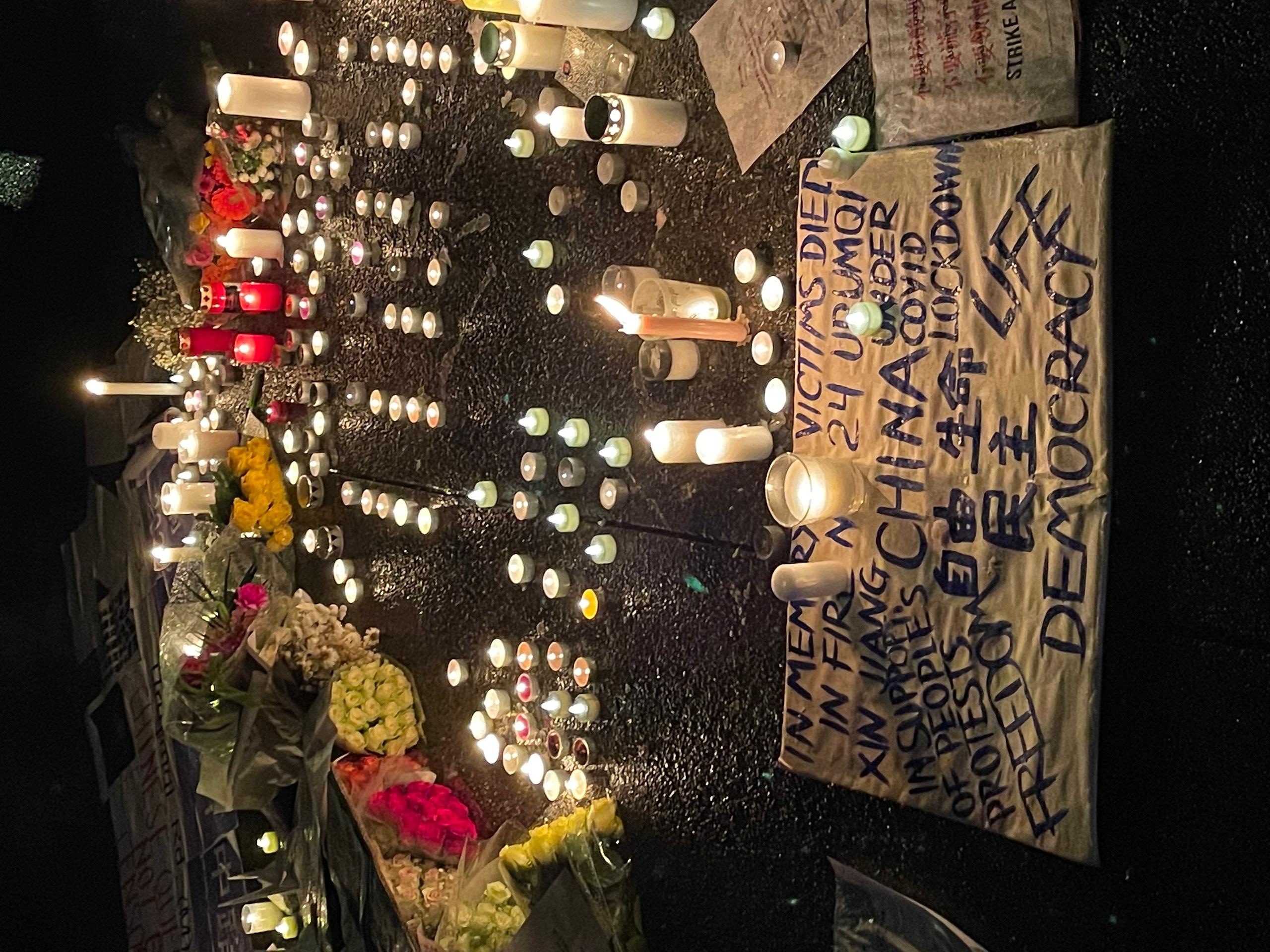

The vigil in Zurich, like ones that members of the Chinese diaspora from Geneva to Melbourne were holding, came on the heels of the biggest demonstrations in China since the pro-democracy protests of 1989. The unrest was prompted by the deaths of ten people in an apartment-building fire in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. While protesters blamed Covid lockdown rules for the tragedy, some were demanding political freedoms and even for President Xi Jinping to step down. For them, the country’s zero-Covid policy had become an emblem of state control over the population.

On the Rathaus Bridge, those who’d gathered lit candles for the fire victims and, like demonstrators in China, held aloft blank sheets of paper in silent protest at limits on freedom of speech.

Lin*, a Chinese student in Switzerland, showed up out of a mixture of fear and anger.

“The police attacked and arrested unarmed protesters for chanting demands or even for holding flowers on the street,” he says. “This is unacceptable. I think it is my duty to speak out for them, for us, and for the future of China.”

The central government, which blamedExternal link “infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces” for the protests in Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and other cities, vowed to “resolutely crack down”. It is not known how many people were detained.

Leading ‘a double life’

Those present on the Rathaus Bridge had to face their own apprehensions about taking a stand. Planning the vigil had led to online disputes – about what their demands to the Chinese state were, for example, or whether the situation of the Uyghur minority, Tibetans and democracy activists in Hong Kong should be among them. In the end, it went smoothly, says Yiyan, and by her estimates drew around 60 people.

But a greater source of concern was the possibility of retribution by Chinese authorities for expressing their views. Bar protests in Switzerland over the treatment of Uyghurs and Tibetans in China, gatherings like the one in Zurich are a rare occurrence. Virtually everyone present wore a face mask to avoid being recognised.

“The biggest risk is that the embassy can identify me and the ‘national security police’ threatens my family back in China,” says Lin. Some overseas Chinese suspect their social media accounts are monitored by security services in China. Relatives of dissidents living in China are also sometimes the target of police harassment, as was the case for one Twitter user in ItalyExternal link who was live-posting images and messages on social media sent to him by protesters in China. Police twice visited his parents in China, who subsequently begged him to stop what he was doing.

“I am in favour of democracy in China,” says Yiyan. “But in real life I pretend to be apolitical – it’s a double life.” She is careful about broaching political subjects when she speaks to relatives in her homeland: “We don’t talk about the protests because everything is monitored.”

The Swiss government says it’s aware that “Chinese services” are interested in the diaspora community, telling parliament in 2020 that spying by China posed a “relatively significant threat to Switzerland”. The Chinese embassy in Bern has denied undertaking surveillance, even though unidentified men, for example, are often seen taking photographs at pro-Tibet rallies, reports the Tages-Anzeiger.

The human rights group Safeguard Defenders recently revealed it had found evidence of overseas “police stations” in 53 countries set up by Chinese public security officials to threaten and intimidate dissidents and even force them to return to China. Beijing has countered by saying the centres offer diplomatic services to overseas Chinese.

To protest in safety

Although the group did not identify any such centres in Switzerland, campaign director Laura Harth says this does not mean Chinese authorities have not targeted Swiss residents. Since 2014 China has run an anti-corruption campaign called Fox Hunt that critics believe also serves as a pretext to target Chinese dissidents living abroad. To date the campaign has seen more than 11,000 individuals from 120 countries being “returned” to China.

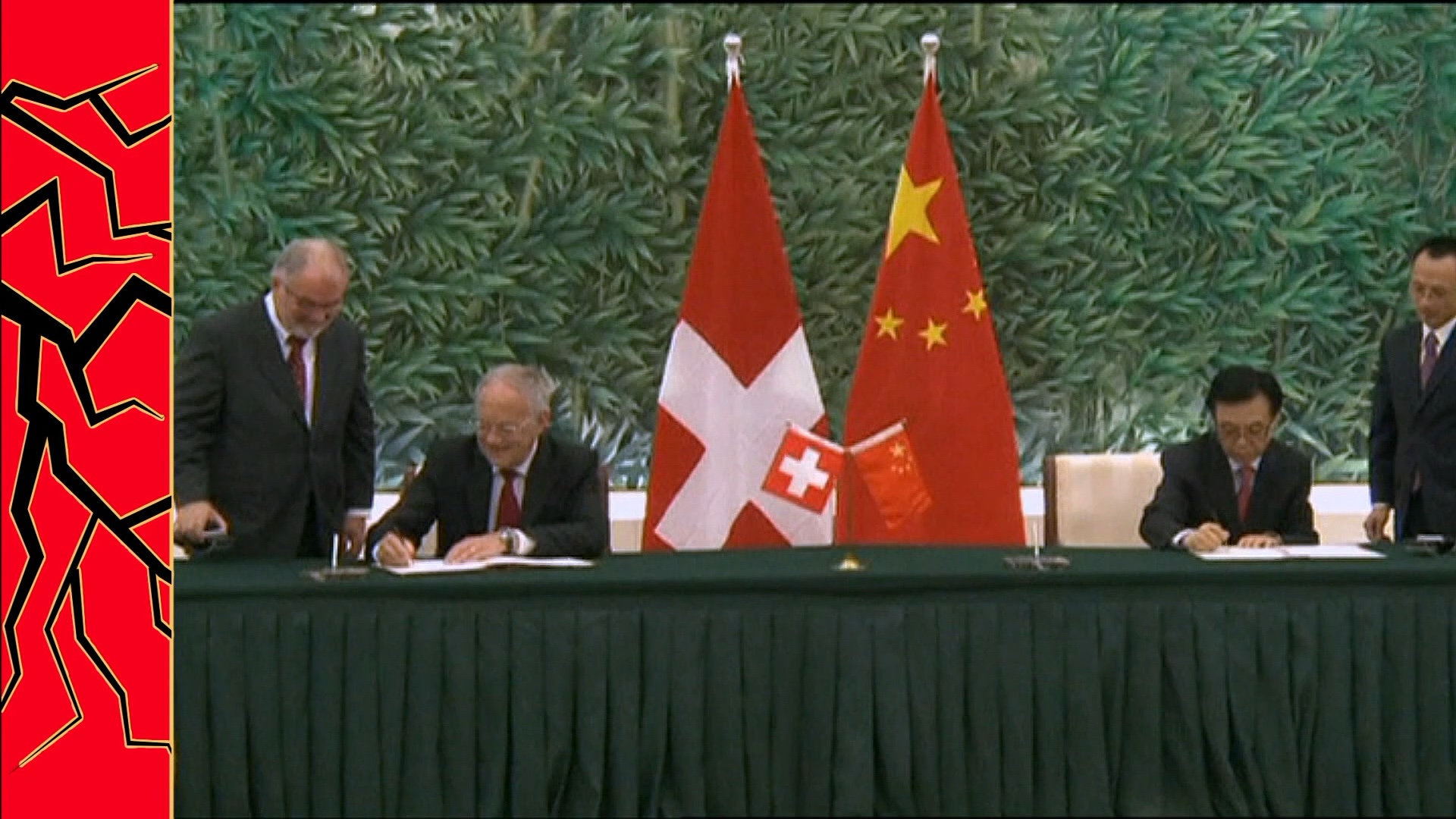

“This means virtually every country in the world is a target of these operations,” says Harth, “making it highly unlikely Switzerland would have been spared – especially considering that previous agreement with the [Chinese] Ministry of Public Security.”

The agreement in question, struck in 2015 with the Swiss State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), caused an uproar when it came to light in 2020. It allowed Chinese security agents to enter Switzerland and verify the identity of presumed Chinese nationals facing deportation.

“That migration deal created a sense of fear [among dissidents],” says Yiyan. “And nothing works better than fear.”

She suspects that some overseas Chinese who reject any opposition to the regime are infiltrating online chats. They try to stir up arguments, she says, to “create divisions and conflicts, and then fish for information.”

Lin too has noticed possible signs of surveillance in online chat groups.

“Someone – I’m not sure if they were hired by the Chinese state or were simply some pro-Communist Party Chinese – tried to impersonate me and ask for information,” he says.

More

How China infiltrates Switzerland

Yiyan wants to be able to use her voice without fear of retaliation against her or people close to her. She hopes the Swiss government will not “make it more difficult and dangerous” for dissidents to voice their opinion by signing more deals with Chinese security officials.

The 2015 agreement expired in late 2020. “There are currently no discussions about renewing the agreement, or signing a similar one,” SEM spokesperson Samuel Wyss told SWI.

‘Not the only one’

In China, the Communist Party has now reversed course on its zero-Covid policy and swiftly scrapped lockdowns, travel restrictions and mandatory testing – sparking a surge in hospital admissions as the disease spreads.

Both Lin and Yiyan say this sudden decision has merely succeeded in placating protesters who wanted to see the back of strict Covid rules. Lin, for one, is sceptical that those who demanded that Xi resign will see political reform anytime soon.

“I believe there’s a long way to go before actual changes take place,” he says.

For some overseas Chinese, however, perhaps the most important change has already taken place.

“Outside China, young political dissidents are becoming united, which never happened before,” says Lin. “At least the flame of 1989 has not died out yet.”

Yiyan has seen friendships form among the people who made it to the Zurich vigil.

“One of the biggest consequences of censorship is that [dissidents online] thought they were alone,” she says. “A lot of people joined an offline protest for the first time – it makes you realise, ‘I’m not the only one’.”

*By request, pseudonyms have been used to protect the identity of the people who spoke to SWI swissinfo.ch.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.