Make English an official language, study urges

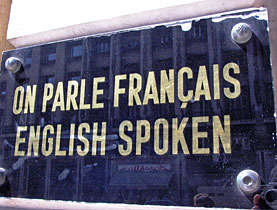

Researchers have suggested making English a semi-official language in Switzerland as a way of attracting more foreign professionals to the country.

Well-qualified foreigners only tend to stay in Switzerland for a couple of years, not always enough time to learn a national language, the study says. Making more legal documents and forms available in English would make their life easier and boost recruitment.

It is just one of the recommendations in a study carried out as part of the national research programme, “The diversity of languages and linguistic capacities in Switzerland”, initiated by the government in 2006 to find ways of capitalising on and preserving the country’s linguistic diversity.

In this final report for the programme, lawyers Alberto Achermann and Jörg Künzli examined whether legal regulations governing language and immigration in Switzerland were compatible with human rights.

They found that Switzerland needed to step up its translation services, especially in some basic situations, such as for foreign patients undergoing treatment in a hospital.

Pragmatic approach

Their recommendation for the government to consider making English “partially official” would include the systematic translation of legal documents in areas such as taxation or employment contracts for staff.

“There would be a pragmatic approach,” Achermann told swissinfo.

“That is not to say that we would establish the right for all English-speaking people to go into any authority and speak English. I think that would go too far. Rather the state would think about in which fields it would be most important to also communicate in English.”

“This would make it easier not only for native English speakers but for a lot of people around the world who are here and have a good knowledge of English.”

He notes that the recommendations are not completely out of step with current policy, citing regulations introduced last October by the government whereby the most important Swiss laws must also be translated into English.

“I think that would be a good solution for the short and the medium-term. It is for people who only remain here for a few years, where it does not make sense to learn another language,” he said.

“I think we are far from having a policy where English would have the same legal status as German or French.”

The move would also bring Switzerland an advantage in international fields where English is the dominant language, the study notes.

Inequalities

He says that although there is an “open” climate in government towards linguistic diversity, not all of their recommendations are expected to be received favourably.

The study also recommends a change to Swiss immigration policy on the national languages, which results in differing approaches for immigrants from inside and outside the European Union.

The study authors state that Swiss legislation sees linguistic competence as one of the “determining criteria” in its policy regarding immigrants, with a new law on foreigners enabling the authorities to make residency permits conditional on a person attending a language course or on possessing adequate language skills.

But this does not apply to citizens of EU member states who, according to Switzerland’s bilateral agreements, cannot be forced to integrate into Swiss society and made to learn one of the languages.

“If you only force the people from the Balkans [for example, to learn a language], it is a kind of unequal treatment,” Achermann said.

“There are quite a lot of people [in Switzerland] who don’t speak a local language sufficiently. That is a fact. Under growing migration and bilateral agreements we will have more people here who are not so familiar with a local language.”

Progressive policies

Instead the study recommends the state develop more forward-thinking and “anticipatory” linguistic policies and provide greater encouragement and incentives for learning the national languages.

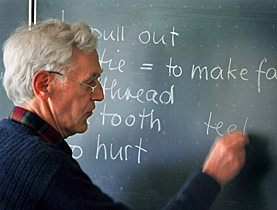

Children speaking a foreign language should be given extra teaching before the school streaming process begins, and the state should reinforce the teaching of the local official language in kindergartens, the study says.

As a possible incentive, the authors also recommend putting immigrants who are fluent in a national language on a fast track to citizenship.

The results of the study are now being compiled in a book with other findings from the national research programme, which the government is expected to review.

swissinfo, Jessica Dacey

National languages:

German (63.7% of the population)

French (20.4%)

Italian (6.5%)

Romansh (0.5%).

Recent immigration has brought a large number of other languages to Switzerland: nine per cent of the population say their main language is not one of these four.

English has become the first foreign language taught in school in several cantons, particularly in German-speaking Switzerland.

A Geneva University study published in November 2008 found that Switzerland’s multilingual heritage gives it a competitive advantage worth SFr46 billion – 9% of its GDP.

Switzerland currently spends some SFr2.5 billion on language learning, mostly taxpayers’ money, or 8.5 per cent of the annual education budget.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.