Daros Latin America reemerges with utopian art against oppression

Tools for Utopia, a new exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Bern, the Swiss capital's fine arts museum, brings together a selection of politically engaged artworks from one of the biggest private collections of Latin American art.

For a few years at the start of the century the Daros Collection promised a golden age for Latin American art with massive investment not only in the collection but also in the renovation of an enormous, dilapidated neoclassical building in Rio de Janeiro to host it – parallel to the foundation’s generous spaces in Zurich.

But in 2015 the dream was over: the project’s initiator, Ruth Schmidheiny, abruptly called the whole thing off.

It was a shock even for the people leading the project, such as artistic director Hans-Michael Herzog. Since then, the Latin American collection has been seen only in scattered pieces loaned to various institutions around the world for exhibitions.

The Kunstmuseum BernExternal link is now presenting the first large-scale show from the collection since the end of the project. However, approaching this rich body of work was certainly a challenge.

“It’s too difficult to tell the story of the arts in Latin America – it’s such a diverse and large continent,” curator Marta Dziewanska tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

“I’m proposing a reading, but it’s just one of many possible readings. I’m not interested just in their aesthetic qualities – they are all obviously beautiful – but in how they are politically moulded. In other words, what these artworks say about the reality surrounding the artists and how they navigated those times of oppression and censorship.”

The starting point is a selection from the 1950s-1970s, the “dark decades” when military dictatorships swept across the subcontinent, leading to another set of contemporary works.

Dziewanska was born and raised in communist Poland and she sees a clear parallel between the artists’ attitudes of those times – their non-conformism and engagement, running serious risks for their arts’ sake – both in Eastern Europe and in Latin America.

But it sounds almost provocative to talk about utopia just as many Latin American countries, and Brazil in particular, are living through a real dystopia.

“Between the 1950s and the 1970s the theme of utopia was very present among artists,” Dziewanska says. “But when we look at contemporary works, created since the late 1990s, we notice how much more modest these utopias have become. They are much more local, and much closer to the queer, feminist and indigenous movements, for example.”

In 1997 Swiss industrialist Stephan Schmidheiny (of controversial fame due to the asbestos affair, in which his firm Eternit was involved) established the Daros Collection with big names of modern and contemporary art (Twombly, Basquiat, Pollock, Warhol etc.) and professional management.

Daros Latin AmericaExternal link was created as the family business expanded its presence in the subcontinent, but separately from the main collection, and run by Schmidheiny’s first wife, Ruth. It comprises about 1,200 artworks from the big names of Latin American art of the past 70 years: Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Miguel Angel Rojas, Doris Salcedo, Cildo Meireles, Antonio Dias and many many others.

Casa Daros, in Rio de Janeiro, was bought for CHF5 million ($5.6 million), and Ruth Schmidheiny spent another CHF25 million on its renovation. It ran for only two years (2013-15) before she pulled the plug.

That decision sparked all sorts of speculation that did not end with Ruth Schmidheiny’s death last year.

SWI swissinfo.ch spoke to former Daros employees and the most plausible explanation is the official one: faced with increasing costs of insurance and maintenance, plus uncertainties related to the security of the collection in Rio, Ruth Schmidheiny simply decided that enough was enough. Casa Daros is now a private school.

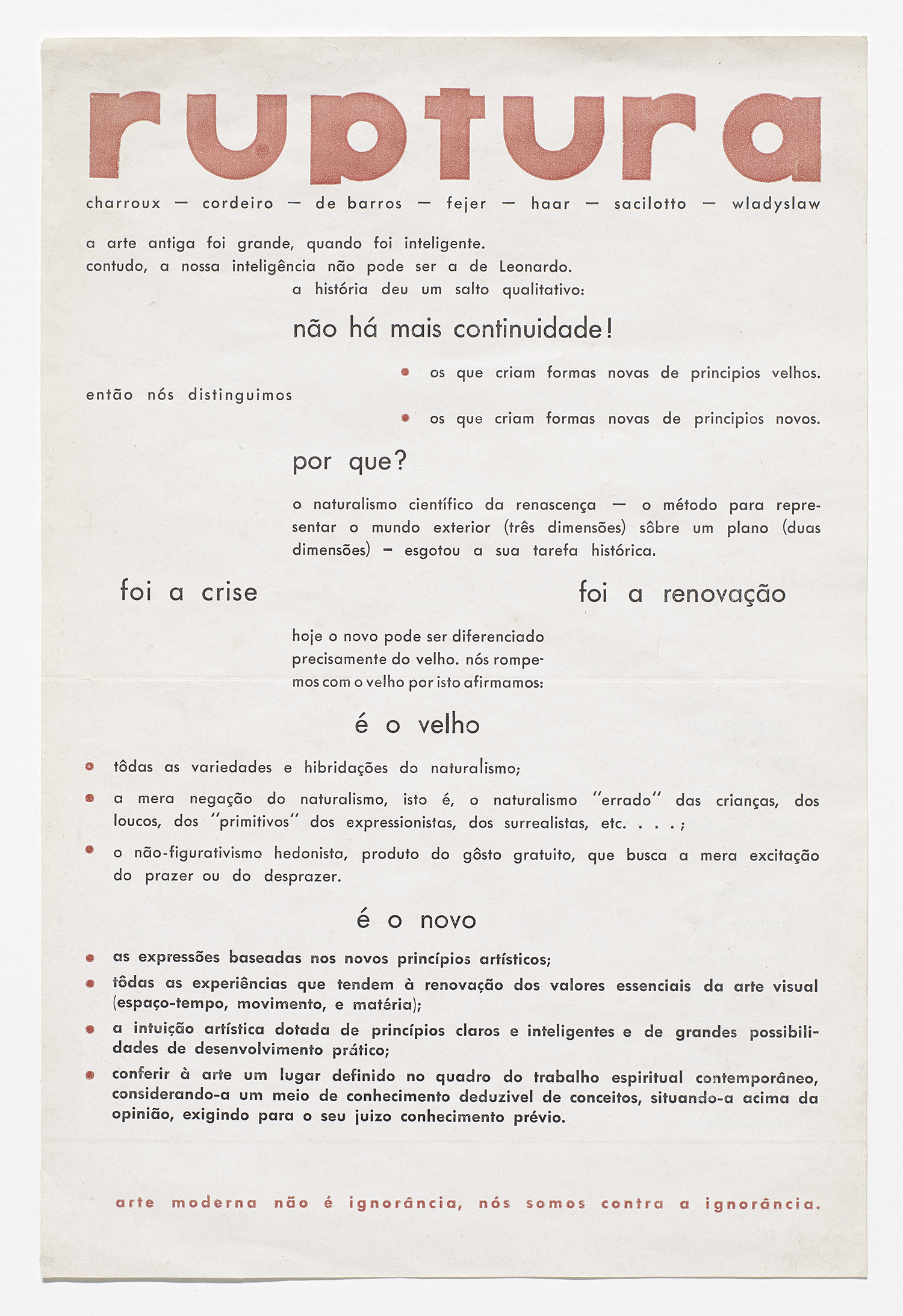

Manifestos

Among the utopian tools of resistance, artistic manifestos used to play a provocative role in post-war cultural debates and gained a prominent space in the exhibition as well as in the carefully designed catalogue.

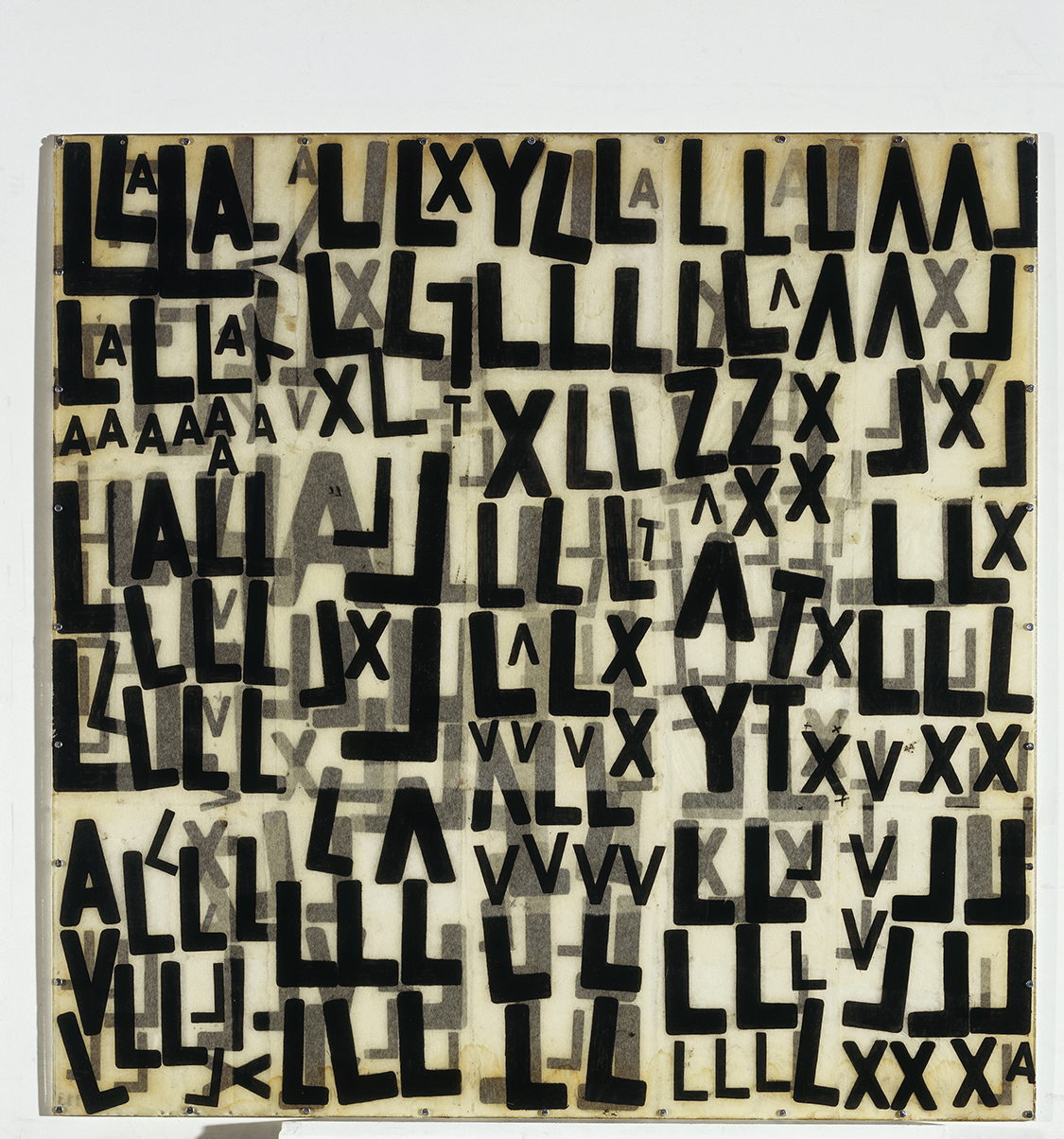

“Artists then were also working in groups, trying to find ideas together,” Dziewanska explains. “It was not about authorship or competition within the art world; they were interested in bringing out new ideas, new vocabularies. They had to go beyond the vocabulary and the alphabet to create a new world; that’s why these manifestos are so important.”

Three Argentinian manifestos of the 1940s prefigure their Brazilian counterparts of the 1950s, a group of poets and graphic artists who launched the Concrete Art movementExternal link with a special attention to the use of typography and graphic elements. This would have a considerable influence on many different media, including advertising.

The power of engagement

None of those utopias ever came close to becoming reality, but the artists kept producing because they couldn’t stop being engaged and dreaming about other possible realities. The times demanded a critical, political posture of the arts – otherwise it would hardly be considered by their peers or the public.

“We need this power of engagement today, and not only in Latin America, but everywhere, and especially here in Europe and in the US, because we are in the middle of a global crisis with local effects,” Dziewanska says.

“In these moments, ideas assume a big importance and even though art is not politics and doesn’t have an immediate impact on reality, it can still change perspectives and provide another vision for the future and for relations between people.”

With a pandemic spreading all over the planet and a climate crisis looming, migrating waves of refugees in almost every continent and regional conflicts exploding for the most varied reasons – land, water, faith, prejudice – it’s quite difficult today to create big new ideas of modernisation or a blueprint for paradise.

“That’s why I decided to go for a title that is paradoxical in its very core,” she says. “Utopia is extremely abstract, but the tools are extremely concrete and precise.”

‘Tools for UtopiaExternal link‘ runs at the Kunstmuseum Bern until March 21, pandemic restrictions permitting.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.